Over the last 9 months I’ve been working on a more concentrated effort to track…

Admin

Updates from the Horseback Sapper

Hello Everyone, you may have noticed some changes to the website, this has been due…

History

Meeting the need for water in the 1917 Desert Campaign

I’ve always been interested in the Campaigns in the Middle East, probably due to films…

The Royal Engineer that improved Water Supply in the Middle East

In the Great War the biggest challenge facing operations in the Palestine Theatre of operations…

Events

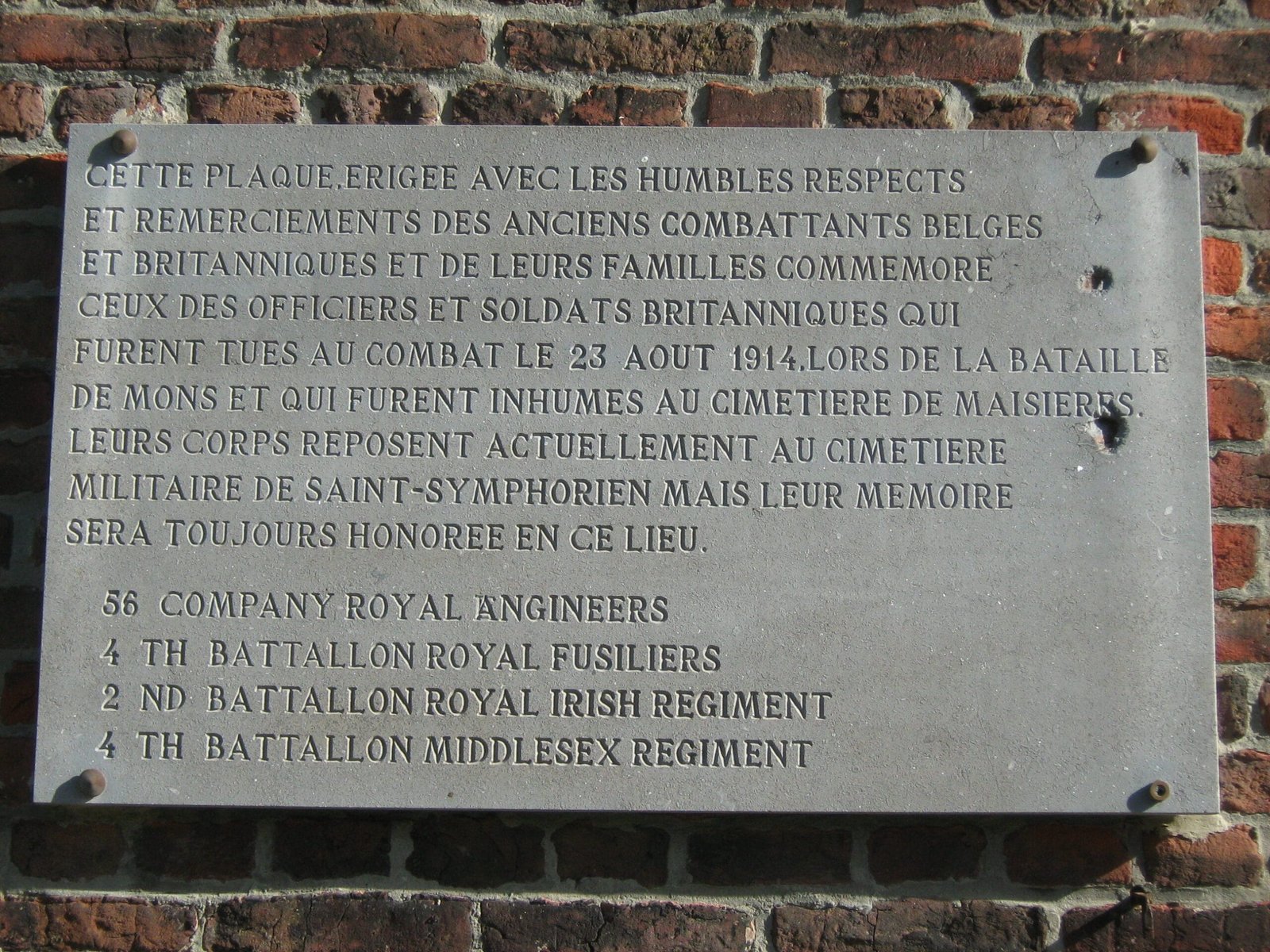

Remembrance Day at Maisieres

This morning I represented the British Forces at the Church at Maisieres at Mons. This…