This is a very short post but it would be remiss not to take the…

Blog

Recreating the 1890 UP Saddle

Nearly 2 years ago I was contacted by Gerard Hogan, an Australian Saddler and conservator…

Blog

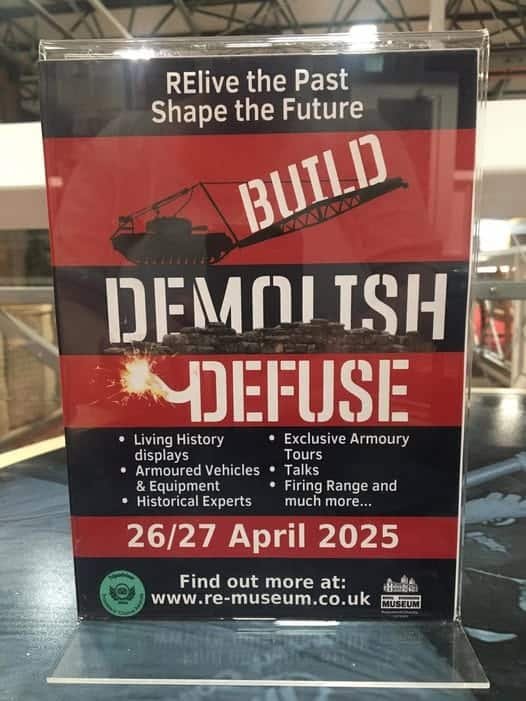

Build, Demolish & Defuse Weekend-26 & 27 April 25

Last weekend in April I was fortunate to find myself helping at the Royal Engineer’s…

Blog

Visiting the Sappers at Railway Wood

During my last 2 weeks in Belgium I thought I would take time on the…

Events

Quick Update – Adding to the WW2 Display

At the moment I’m being kept busy with the transition from being overseas to coming…