Sapper preparations for Beersheba 31 Oct 1917 (Third Battle of Gaza)

In 1917 things were picking up pace in the Middle East against the Ottomans. The Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF), made up of British and Imperial units, had advanced out of Egypt, across the Sinai and had launched attacks against the Ottoman defensive line that was anchored against the town of Gaza.

Wire mesh laid to provide foundation for road construction across the soft sand of the desert, These were laid by Sapper units across the Sinai and on the approaches to Gaza. The First and Second offensive against Gaza has failed1, but with a change of command from General Murray to General Allenby there was a change of approach.

General Sir Edmund Allenby and Lt General Sir Harry Chauvel at a medal presentation for the Desert Mounted Corps The aim was now to put together an attack on Beersheba, which was on the eastern end of the Ottoman defensive line, further into the desert and defended by significantly less troops, but to give the impression that this was a feint/ deception as a precursor to another assault on Gaza. The ottomans believed that Beersheba could not be attacked by a large force in strength due to the lack of available water in the area and as such any sizable force would need significant logistical support to sustain it in the field.

And to be honest they were not wrong, Allenby recognised this and realised for his plan to work he would need water supplies as far forwards as possible and stores and supplies as well. The most efficient way for that was to use railways, as they had done for the assaults on Gaza, but for Beersheba there were none existing just as the availability of wells was extremely limited, so everything would need to be built from scratch.

Logistics and Railways.

While it was accepted that water would be the priority it needed to work hand in hand with the creation of the railways. (Water was essential for Men and horses but also for the locomotives, the desert environment put massive limitations on the railway engines so a good supply of water was vital). The Sappers and Egyptian Labour corps of the EEF had already created rail lines from Egypt to the Gaza battle front so it was decided to construct a spur from the Gaza Railway line out into the desert.

The branch line construction started at Rafah 10 days prior to the attack. the line was laid heading east towards Esh Shellal and was constructed by 115th and 116th Field Companys Royal Engineers, half a battalion of Sikh pioneers and 400 labourers from the Egyptian Labour Corps (ELC). The construction of the railway was kept to last safe moment to prevent the Ottoman’s discovery and the majority of the work was carried out at night while the Infantry and Mounted units provided a forward protective screen.

The 266th and the 116th Field Company Royal Engineers then constructed the Imara Station which provided the supply head for 155th Infantry Brigade laydown area. This Brigade then provided the screening troops to allow the construction of line forward to Karm. This would be completed on the 28th Oct and provided the furthest eastern Rail head for supply for the attack, this meant that the British and Imperial forces would have a rail head only 12 miles from Beersheba.

A spur to the rail line was also constructed from Esh Shellal 4 miles south to El Qamie. this would provide supplies to the area occupied by 60 Division.

In 8 days the Sappers with Sikh pioneers and Egyptian labours constructed 26 miles of railway, mainly at night and trying to maintain tactical secrecy.

As mentioned earlier the main task for the Sappers in preparation for the attack on Beersheba was to ensure that water could be provided for the large quantities of Men, Horses and as previously mentioned the railway engines.

The intention was that the Desert Mounted Corps would carry out a flank attack on Beersheba from the East of the town, to achieve this in secret the plan was to push out to the south and then sweep wide to the east hopefully unobserved but this route would take the men and horses the furthest away from water for the longest period.

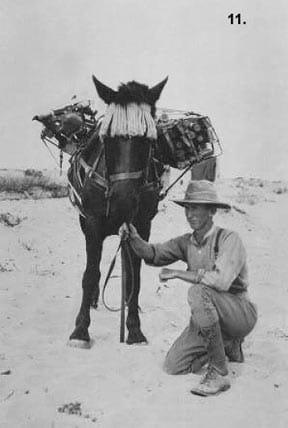

6th Bn Australian Light Horse – Take note of the quantity of equipment on the saddles of the horses and men. While they were aclimatised to the desert the need for water was key. On the 21 Oct 1917 the mounted sapper unit, 10 Field Troop RE, headed out into the desert and established a shallow well at Bir el Eseni, once established this would provide water for 9000 men and horses. With that task complete, the Troop headed 8 miles further south to Wadi Khelasa, near the ruins at Khelasa and constructed another shallow well and waterpoint by the close of 22nd Oct. This was already for the Corps to replenish water prior to the last stage of their approach ride to the east of Beersheba.

As the railway line from Rafah pushed forward Sapper units constructed more wells, initially as shallow wells and then enhanced further to deep wells.

THE BRITISH ARMY IN THE SINAI AND PALESTINE CAMPAIGN, 1915-1918 (Q 12622) Royal Engineer’s pumping water from the subterranean fountain from which Solomon’s Pools reserve are fed. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205067244 by the 24th Oct 155 Infantry Brigade had taken position at El Imara to provide protection to the rail line construction going forward to Karm. A section (a troop size unit in modern Royal Engineer units) from 436 Field Company RE had constructed wells and a water point for the formation.

by the 26th Oct the remainder of 436 Field Company had constructed wells and water points for 60th Division in the Tell El Fara and El Qamie areas.

Major water point with canvas water troughs in radial around the well and what looks like water tanks being constructed in the distance. As part of the final preparations for the attack 9 Field Troop RE moved forward to Goz El Basal, just south of the Karm Station on the 27th Oct to construct a well and water point for the Australian Mounted Division who would provide the troops for the forward defence of the rail head and were located at El Baqqar. These troops were in place by the 27/28 Oct.

The final part of the preparation was for 437th and 439th Field Company RE to go forward and construct infantry defences and 21 defensive outposts. These defences help to protect the troops of the Yeomanry when they were attacked by a Turkish force on the morning of the 27th, who were defeated and this allowed construction on the rail head to continue.

THE TURKISH ARMY IN THE SINAI AND PALESTINE CAMPAIGN, 1915-1918 (Q 58657) A Turkish cavalry patrol on the move in Palestine. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205307837 It can be seen that Sapper units were vital to the operation to attack and take Beersheba, often required to push out well ahead of units to have waterpoints established ready for the troops and horses to arrive.

The Battle of Beersheba on the 31 Oct 1917

The attack was carried out by the following units:

HQ Desert Mounted Corps

ANZAC Mounted Division

Australian Mounted Division

Yeomanry Mounted Division

10th Division less the 30th Brigade (Infantry)

53rd Division with the 30th Brigade (infantry)

60th Division (Infantry)

74th Division (infantry)

The town was attacked from the west by the 60th and 74th Division. The ANZAC Mounted Division moved round to attack from the East.

The aim of the mounted troops was to circle round to the east and to attack from the rear and to secure the towns wells intact.

The attacks by the 60th and 74th initially made good progress but were slowed as the day progressed. It was imperative that the town be taken that day as the soldiers and the horses of the entire Corps had been without water replenishment for nearly 36 hours.

Late in the afternoon of the 31st Oct, the 4th Australian Light Horse Brigade was tasked with attacking Beersheba.

The Australia Light Horse are not a cavalry regiment, but rather a Mounted Infantry Unit, which would normally advance mounted and then dismount and put in the final attack dismounted as convensional infantry.

However the Brigade decided to do something different and rather than dismount they continued mounted and moved from the walk to the Trot onto the Canter and then to the Charge. The Turks were taken by surprise with change of tactics as the Australians managed to break through the defences and to capture the town by 6pm.

The charge of the Light Horse at Beersheba is rightly celebrated by the Australians. Their assault achieved surprise on the Turkish Troops and their German advisors at the cost of 31 Light Horsemen, but it is important not to forget the men of the 60th and 74th Division that had had a hard and thirsty day fighting on the West of the town.

So if you have an opportunity this evening lift a glass to the brave men and horses of the Australian Light Horse, the 60th Division and the 74th division and have a drink on behalf of the dusty and thirsty men and horse who fought at Beersheba in 1917.

Footnotes:

- 2nd Gaza was almost a break through but General Murray called a halt and withdrawl just at the point when the battle would have been won. ↩︎

The Signals Telegraph Cable Saddle

Several years ago when I started to learn about the various types of military saddles I would try and find as many images of British Military saddles as I could. Eventually I had built up a fair collection of images of the different types and also of the UP pack saddle with different types of loads fitted.

I eventually came across a rather poor quality image of an Indian Soldier leading a Mule in Gallipoli and it looked as if the Pack saddle on the mule had been modified to hold a reel of telegraph wire. The poor quality of the photo meant that it wasn’t clear if the saddle was one of the following:

- a modified Pack Saddle

- a modified UP Saddle (which occasionally happens)

- A bespoke saddle for signals units

At the time I was helping a couple of historians with some of their research into equipment of cavalry and mounted units and I enquired with them if they had ever seen anything like this before and if they knew what is was?

The responses were pretty poor to be honest, ranging from “I’m not interested in that type of detail” to “it doesn’t look like a cavalry item, so it can’t be important.”

It was a bit of a hard lesson for me and helped to shape some of my views on the relationships between Historians, Battlefield Guides and Reenactors. It also made me start to understand where each of these groups have gaps or limits in knowledge or levels of detail.

Not to be daunted I continued to search for information on the different types of saddles and how they were configured and modified, always keeping an eye out for hopefully a clearer image of the “Cable Saddle”

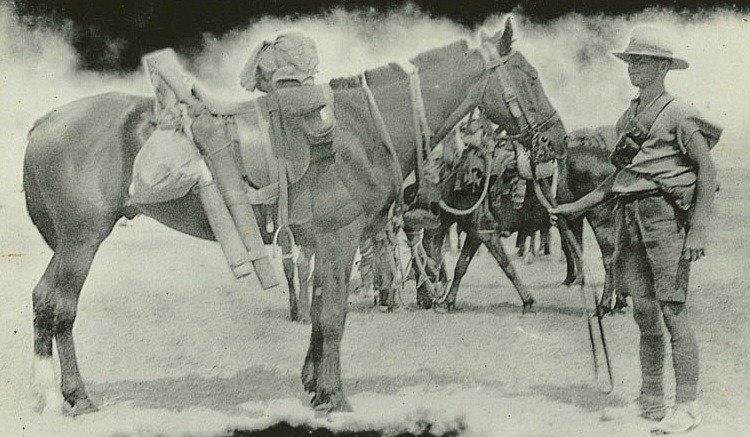

The break through came over this summer as I was researching the Heliograph bucket for the UP saddle and I came across this really clear image of the Saddle with a Canadian Engineer Unit.

While it seemed to me that saddle configuration may have started as a “Heath Robinson” modification of a UP Pack Saddle it appeared to have become a formal Pack Saddle variant, which may have accounted for the slight variations in the saddles in the two photos. I suspected that the saddle shown in the photo from Gallipoli was probably one of the early versions, while the one shown below is a more refined model. My assumptions may well have been influenced by the quality of image rather than detail of the saddles!

It was purely by chance when I was researching the Heliograph saddle buckets that I got chatting via messenger with the a chap called Jonathan Paynter who had an original set of heliograph and telescope buckets and as we chatted he told me that had done a set of drawings of the Cable Pack Saddle, from this I became aware of the cable types used with the saddle.

It is clear that the saddles shown in the two photos had different types of cable, the photo of the Indian Signaller with the mule has a large drum fitted and a different front arrangement, my initial guess was that this may be D1 type cable. However a bit of research into Telegraph cable types provided some real bonus details. The Royal Canadian Signals Website provided the detail of the differences in the cables, a link to the website is below. From the website it states that D2 cable is a lightweight usage telegraph cable and D3 is heavy weight usage, with D2 cable being ideally dispensed from Pack equipment (Bingo!). It is also interesting to note that D2 Twin cable is available. Having looked at the website details I discounted D1 cable as an option as it is a lighter weight cable and only single strand.

D2 single strand is 20-25 lbs per mile and comes in half mile reels and has a breaking strain of 140lbs, D2 twin is approximately 50 lbs per mile with a breaking strain of 250 lbs.

D3 single is 40-50 lbs per mile with a breaking strain of 196 and D3 Twin is 84 lbs and a breaking strain of 354 lbs. Based on that information the larger reels appear to be the D2 & D3 twin Cable reels.

The chat with Jonathan gave me more details and showed that the saddle would carry upto 6 reels of Cable (D2 or D3 type cable) and these would dispense a single reel out over the back of the Pack Horse/ Mule and would allow the signals team to then place the cable in position. I would also suspect that where twin cable is used they would cut the load to 3 cable reels due to both weight and also the space occupied on the saddle.

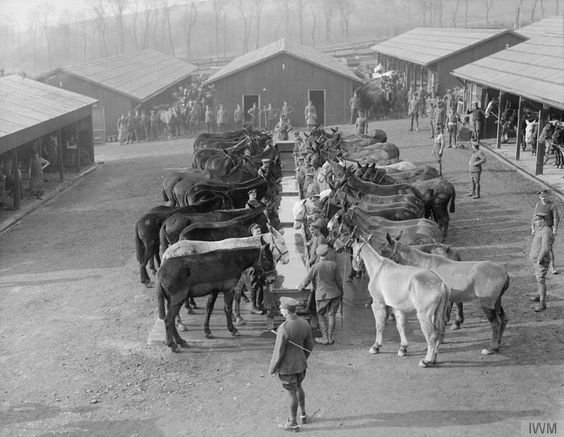

The Royal Canadian Signals website also has a cracking photo section and in there I was able to find clear photographs of both versions of the Cable Saddle.

The pattern saddle matches the one in the Gallipoli photograph

a side on view of the cable saddle matching the one shown with the Canadian signals section photo.

Pack horses being training with the Cable Saddle and dispensing the cable A link to the photo section of the Royal Canadian Signals Website is below, (its a cracking website so please go and have a look round it.) But the real benefit was that it showed that both types of saddle were proper variations of the Cable saddle and both appear to be able to dispense D2 and D3 cable (single and twin). I will make an assumption that the larger reel in the Gallipoli photo is a reel of twin cable.

So what is the purpose of the Telegraph Cable saddle? While the Cable Wagon would rapidly dispense cable along roads and tracks, it would have difficulty moving the cable onto the next stage of the journey going forward. Effectively the Cable wagon would operate at Signal Company/ Squadron level and above, and also with dedicated Cable Laying Units, and they were Divisional level assets. The Cable laying pack horse would be a Brigade level asset and be operated by a Signals Section or Signals Troop connecting Brigade HQ to Regiment/ Battalion HQs and would be able to move over more damaged or constrained terrain. The final connections forward would then be undertaken by men unreeling cable by hand.

Indian Corps Signal Section putting up a telegraph line, Merville, France.

Cable being laid by hand in Palestine While this may seem like it is a small deviation from my usual focus it does tick a couple of boxes for me. Firstly it is a variation on the pack saddle and part of the UP saddle family.

Secondly and importantly it is another element of information that debunks the assertion that Engineering can not be carried out from horseback. With Signalling, at this point in time, being an Engineering task this is an almost perfect example of engineering being delivered (dispensed) from Horse Back.

It’s surprising what you find when you go searching for other things!

References:

Royal Canadian Signals Website:

- details for Cables – http://www.rcsigs.ca/index.php/Field_cable

- Images from the Great War – http://www.rcsigs.ca/index.php/Photos_-_The_Great_War

A Refurbished 1912 UP (Swivel Tree) Saddle

Since I started doing Great War riding and re-enacting/ living history one of the things that was always pushed was the need to ensure that I had an appropriate saddle. Be that an Officers pattern saddle or an 1902 UP saddle.

The more that I got into Great War Living History and the more that learned I found that there were various patterns of the 1902 saddle and also that the Universal Pattern saddle had evolved over time, all of which made sense.

As part of that learning process I encountered the 1912 Universal Pattern Saddle. While this looks very similar to the 1902 Saddle the difference is that the Steel Arches of the Saddle are hinged and this allows the wooden boards of the saddle to move and rotate in a limited manner. The purpose of this was to create a Saddle that could fit all varieties of horse and mule. Where a unit with 1902 UP saddles would need a variety of sized saddles (generally Medium (Size 2) and Large sized arches (Size 3)) the adoption of the 1912 UP saddle was meant to do away with the need for holding spare saddles or arches of different sizes.

For Example a Royal Engineer Field Squadron was meant to hold saddles sized at the percentage rate of:

- Size 0 – 0% (this size of saddle was only issued to Mounted Infantry who tended to be mounted on Cob sized horses (less than 15 hands high)

- Size 1 – 10% (Small Horses)

- Size 2 – 50% (Medium Horses)

- Size 3 – 40% (Large Horses)

While this system was fine in peacetime or early in conflicts it was recognised that horses may lose condition, or change the muscle definition when worked/ exercised. in the initial instance some of this variation in the horse can be managed with the way that the horse blanket is folded but this is not the ideal. Also there is the fact that when remounts are provided (horse battle casualty replacements) they may not be of the same size as the horse that they replaced and as such would need different saddles.

The aim was that the 1912 UP saddle would solve this issue by providing a saddle that was “flexible” to meet the sizing and any changes in the physical condition of all horses.

However it wasn’t widely issued with British Units. There are comments that state that the Swivel connection was a point of weakness in the saddle and as such it wasn’t really adopted. This isn’t the case. Firstly the saddle was widely used by the Australian mounted units, particularly the Australian Light Horse and it was viewed as an excellent saddle, very suitable and robust for military usage, both fully loaded and on it’s own. The second, and probably the main reason is that by the time it was accepted for use by the Army the Great War had started and the reality was that the Army already had stocks of the 1902 UP saddles and their components. Also the fixed Arches of the 1902 were considerably easier to manufacture quickly and less complicated when constructing the saddles in comparison to the 1912 UP..

In terms of the Australians, they would have less stock of the older pattern saddles and may well have been in the process of “re-tooling” for the 1912 when the war came and the expansion of the Australian Army and in particular the Mounted Units it would have made sense to just make the new pattern of saddle.

It is certainly the case that most examples of the 1912 tend to be found in Australia.

Over the last 18 months I’ve been linking in with Gerard Hogan in Australia, a Saddler and historian that is working with the Australian Army Museum, and the opportunity arose to obtain a 1912 UP Saddle for my own collection, both in terms of being able to use it for riding as well as for Living History displaying.

The basics of the saddle, such as the arches and boards were originals (from different original saddles) but the leather work would be new. I was asked if I wanted the leather work marked to a particular unit, so I kept it basic and asked that Gerard mark it with his own marks and also with unit marks appropriate to an Australian unit.

To that end there are stamp marks with Broad Arrows but with GH stamped next to them (Gerard Hogan) and also all parts stamped for 10th Battery Australian Field Artillery.

Part of the refurbishment process is to do some treatment work on the saddle. I was under very specific orders not to stain the leather dark, but to keep it the light tan colour as was the case in the Great War, the darkening of the leather was tend to a mix of it being used over a 100 years and also it not being properly cleaned!

So the orders were to make sure that all of the leather was fully coated with dubbing, I have been using Elico’s Gold Label Brown Dubbin, which has been ideal as it is easy to work into the leather.

So what is the plan for the saddle? The aim is to use it for riding and displays. My horse, Rosey, has high withers and back length that does not suit any of the UP saddles that I currently have:

- The 1890 UP is 24″ long

- The 1902 UP is 23″ long

- The 1902 UP (HC variant) is 22″ long and fits her back but not her withers and shape of her sides.

- The 1902 UP (Indian variants) are 21″ long, they fit by length but are too narrow.

- The 1912 UP is 21″ long and has the movement in the boards to hopefully fit her.

The 1912 will also fit Meg the mule. Also it allows me to show the variation and the evolution of the saddles over time. I will probably look to set the 1912 up as either a typical fit out for Australian Light Horse or for a Driver with the Sappers, Gunners or Army Service Corps, with a Greatcoat strapped to the front of the saddle and plain shoe case (and the Rifle to be slung across the back of the rider.)

Overall, a great addition and once I’m back in the UK full time I’ll be able to get it set up appropriately and hopefully get out for a plod in the local area with either Meg or Rosey using the saddle. More to come……

Signals Equipment and the UP Saddle

During the Great War, signals was an element of Royal Engineers with some parts devolved or shared out to different cap badges including the Cavalry.

Now signals are not a particular interest of mine but they do have some very particular elements of equipment that link into the Mounted Units or have resulted in some interesting horse and saddle equipment.

I will confess that the idea for this post came about when I came across an interesting photo that was unusual for a couple of reasons.

The reason that I first look at this image as it is so unusual to find a rider of a horse in the Great war to be wearing 1908 Equipment (Webbing). The next thing was that item that was strapped next to the rifle bucket, I’d never come across that before and my initial curiosity thought that I may well have been a trials piece of kit or something linked with the Hotchkiss Machine gun, but I couldn’t find anything that related to that.

It was purely by accident that I came across another photo with a similar set up and it referred to it as “Signals Flags Bucket”.

With a little bit more digging and research I found out that this was partially true. The reality is that they form part of a set that are fitted to a saddle and they are for the Heliograph signals equipment. The buckets are fitted to each side of the saddle and are designed to carry the heliograph tripod, signals telescope, and signals flags, thus allowing a Cavalry Regiment to carry signalling equipment in the field.

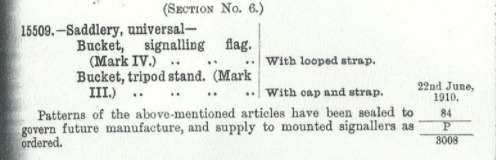

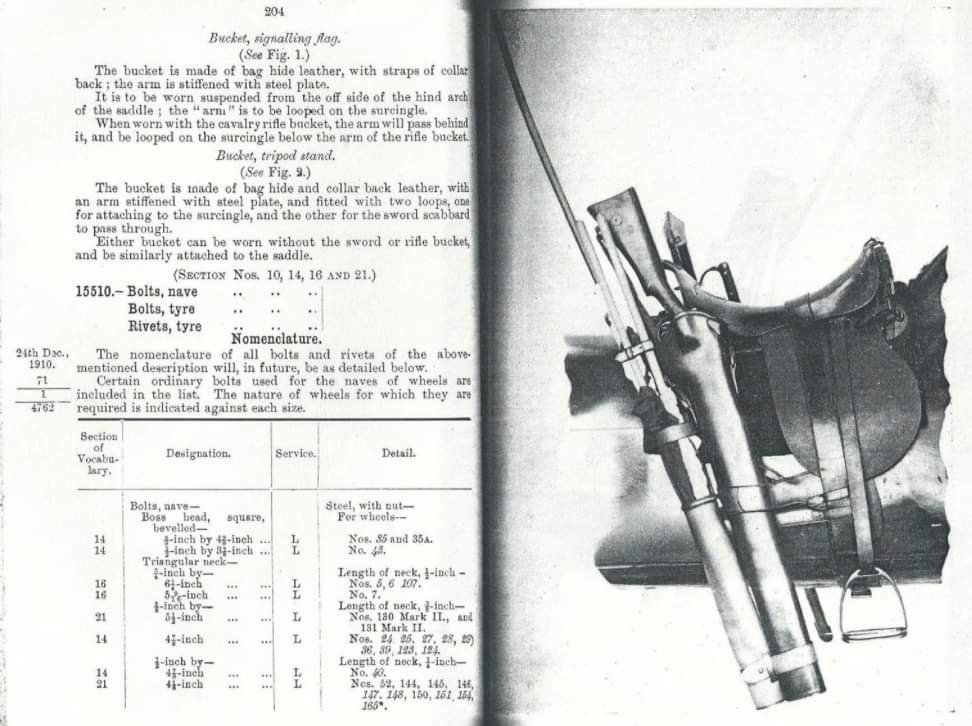

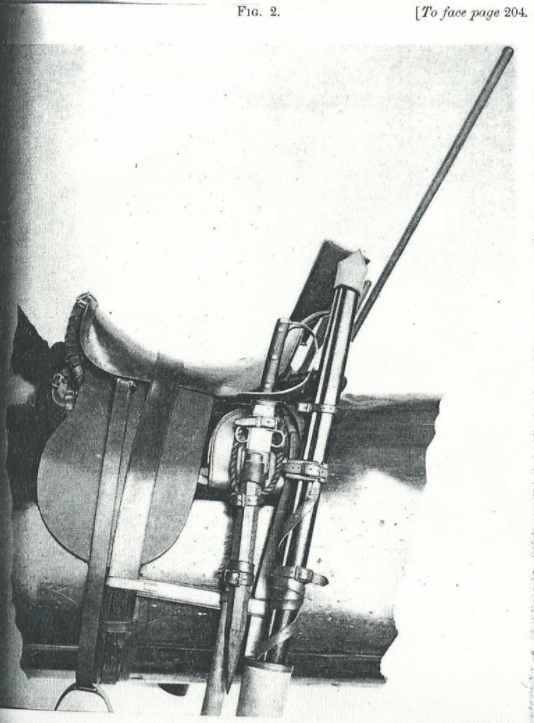

Signallers of the East Riding Yeomanry using a Heliograph and observing telescope in 1917 I went looking to get some more information on the heliograph equipment and manage to track down the information on the buckets in the List of Changes (LoC) and as part of that it had 2 excellent images of the buckets loaded with equipment fitted to a UP Saddle.

The mirrors and the “headset” of the heliograph would be stored in a leather case with a leather or webbing strap and were carried by the signaller while mounted.

I found that there is a very good facebook group that deals with the Heliograph equipment, of which there are a couple of posts about the use of the Heliograph by mounted units and even some images of the buckets, the photo below is a brilliant image of the two buckets, in what looks like excellent condition. They are owned by a chap called Jonathan Paynter and he states that they are stamped 1914. The Facebook group is the British Heliograph Club https://www.facebook.com/groups/776510812960897/

The left is for the telescope stand and signals flags, the right is for the Heliograph tripod. The Straps/loops at the top of each bucket would have gone around the rear arch of the UP Saddle, allowing the bucket to hang down, in the same way as the Rifle Bucket and the RE Tool Bucket does. On both you can see the leather steadying strap (in the centre of the buckets) that would have reached across to the Girth strap of the saddle and leather loop at the end of the strap would have allowed the buckets to be secured/tied by having the surcingle strap pass through the loop.

On the left bucket the strap at the bottom of the bucket is a short retaining strap to help tie the flag bucket to the Rifle bucket next to it. On the right hand bucket centre strap you will notice a smaller loop, this is to allow the scabbard of the Cavalry Sword to pass through and again this also adds to the stability of the equipment on the saddle. Admittedly that is quite hard to see in the LOC photo above as that has the picket peg secured above the sword scabbard (as it should be) but also over the top of the leather loop on the heliograph tripod bucket

The heliograph was an excellent piece of equipment and was used through out the army from the Victorian period and the Survey Squadrons of the Royal Engineers were still using it through to the 1980s when they were out doing large scale survey works.

The size and weight of the equipment also made sense that Cavalry units should have access to it and that it should be available in the field rather than being in the unit baggage/ stores wagons. From what I can find it was issued at the rate of 2 heliograph sets per cavalry regiment.

Australian Light Horse signals team 1918 in Palestine

Unit unknown but these signallers are only using the Flags buckets. the lack of rifle buckets on the saddles suggests a mounted infantry unit (they often slung their rifles on their backs)

So to come back to my original puzzle, I still don’t have an answer as to this rider wearing 1908 equipment but I have at least learned about what the additional equipment is, and also learned that whoever loaded the kit put the heliograph tripod in the wrong bucket! Oh well everyday is a school day and it is always great to use old photos to broaden your knowledge through investigation and research.

A great place to stay on the Somme – Le Logis d’Anne-Sophie

Firstly this post is not a “paid for post” or sponsored post but simply a personal recommendation for somewhere that offered a great place to stay and brilliant service.

A few months ago I was down on the Somme and decided to stay overnight and didn’t want to stay in Albert. I was tracking down several of the “Men of Hartshorne”, visiting Delville Wood and also trying to locate 2 river crossing points where 3rd Field Sqn RE put in bridges for the Battle of Amiens on the 8th August 1918. So it was a visit with plenty of things to do.

Having searched for somewhere to stay I found a cracking place at the village of Chuignolles. The property is a very impressive country house and there are 2 rooms for renting and the owners provide an excellent breakfast.

Le Logis d’Anne-Sophie, is a great place. It’s quiet and very comfortable and the use of the lounge with the very warm open fire was just what I needed so that I could spread out the maps and books while I planned my next day activities.

It is Bed and Breakfast, and I must say it is a bloody good breakfast – Home made Brioche, with home made plumb jam which I can highly recommend . The village is quiet and you may need to head to the surrounding villages and towns for an evening meal but as I had brought my own evening food (due to being on this bloody diet) that wasn’t a problem and the owners set a place on the dining table for me to eat.

It was also interesting chatting with Anne-Sophie’s husband, Bruno, that he mentioned that the house had been used by the Germans in both wars. This was particularly interesting as some of the Armoured Cars of the 17th Armoured Car Battalion came through the village on the morning of the 8th August 1918 and engaged a German MG Company in the village, considering the house is on the main junction in the village the chances are that the house was in the thick of it. It would be an interesting side project at some point to research into the events of that day and what happened in the village.

Overall I can say that Le Logis d’Anne-Sophie is probably an ideal place to stay if you are looking at researching and exploring the Amiens 1918 battle area and if you just want a quiet but very comfortable place to stay when visiting the Somme area at any time of the year then give them a visit.

or contact they direct – logis.annesophie@gmail.com

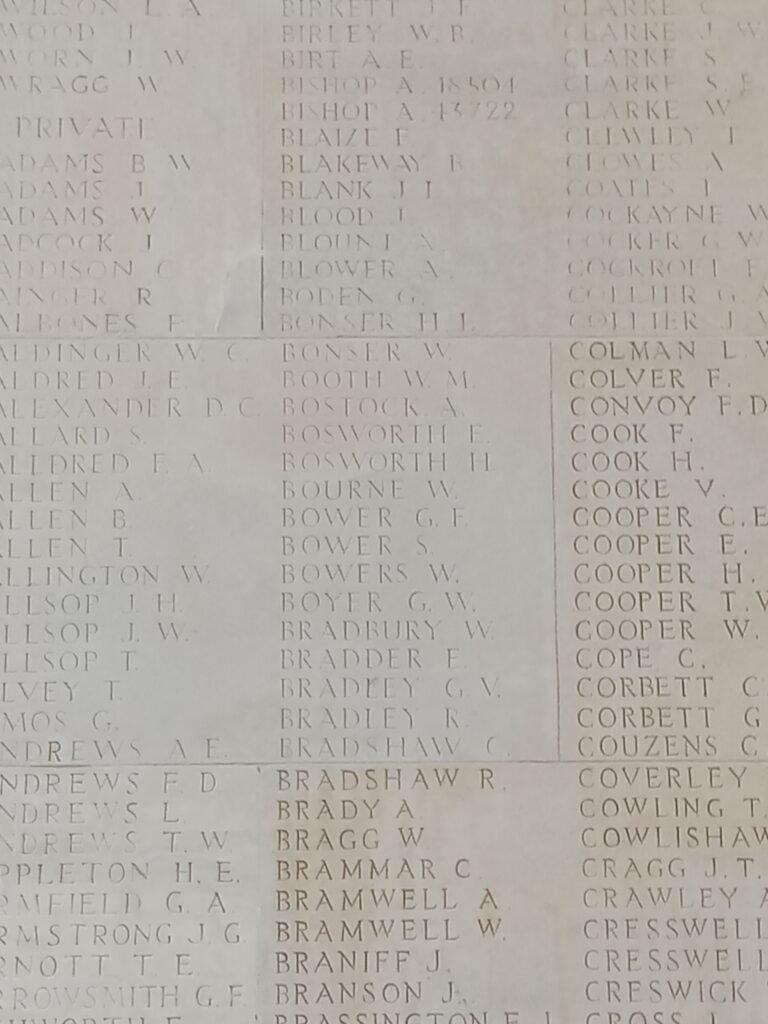

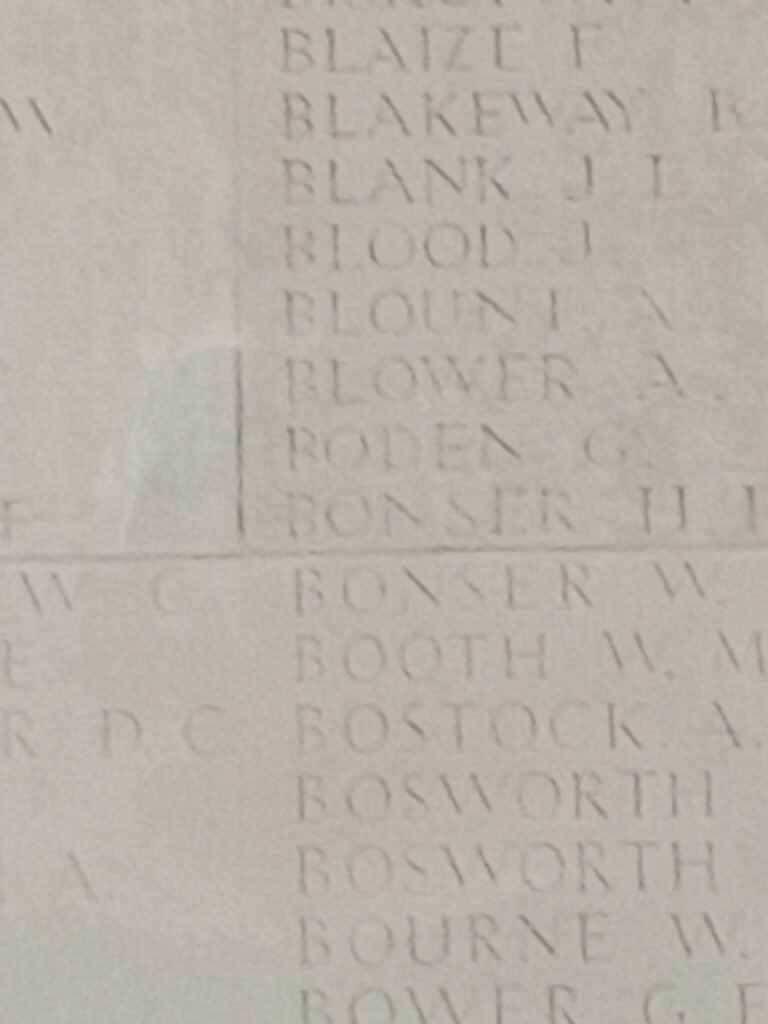

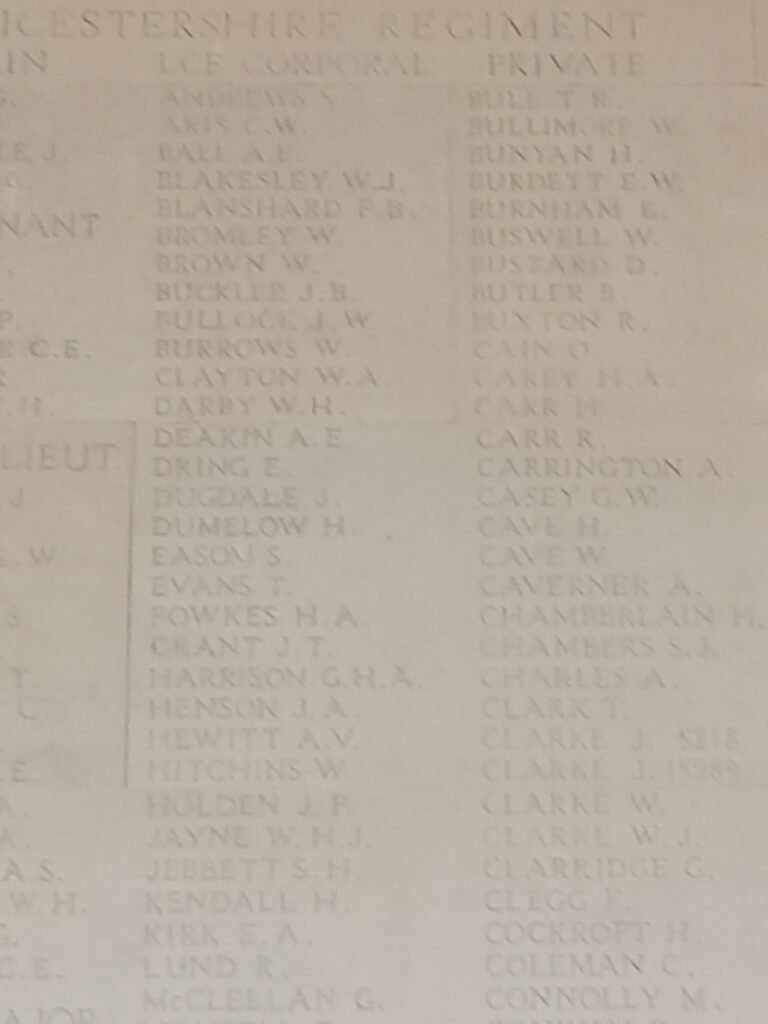

The Men of Hartshorne – Part 2

Over the last 9 months I’ve been working on a more concentrated effort to track down the graves or memorials of the individuals that died in the Great War that are named on the village war memorial. As stated in the original blog post (https://horsebacksapper.co.uk/?p=798) about the “Men of Hartshorne” there is a really good document that has the details of each individual that is named and also background information.

Of all of the men named there are 3 which currently that I can’t get to, 1 in Kenya and 2 in Turkey but I am looking at possibilities to get the Graves photographed by people in those locations.

In addition there is one other that I have not visited as it is a bit further away from my current location and I’ll need to try and link them with some more activities or battlefield visits. I will get them but not just yet!

The other thing that I will try and do is also give an indication of what battles they may have been killed in. Now there is no guarantee that this will be an accurate assumption of the point at which they died, the reason for this is that some of these soldiers are buried in cemeteries that will have been located next to field hospitals, clearing stations or aid posts or they are in cemeteries that are amalgamation of smaller burial sites. So these are assumptions and educated guesses. If anyone has more accurate details then please let me know so that I can update the information.

Private John Warden Allen, 25th Battalion Royal Fusiliers

Died of Wounds on 26th May 1916 and is buried in Nairobi South Cemetery.

I’ll try and get one of the Royal Engineers based in Kenya to visit the grave and take a photograph of John’s headstone.

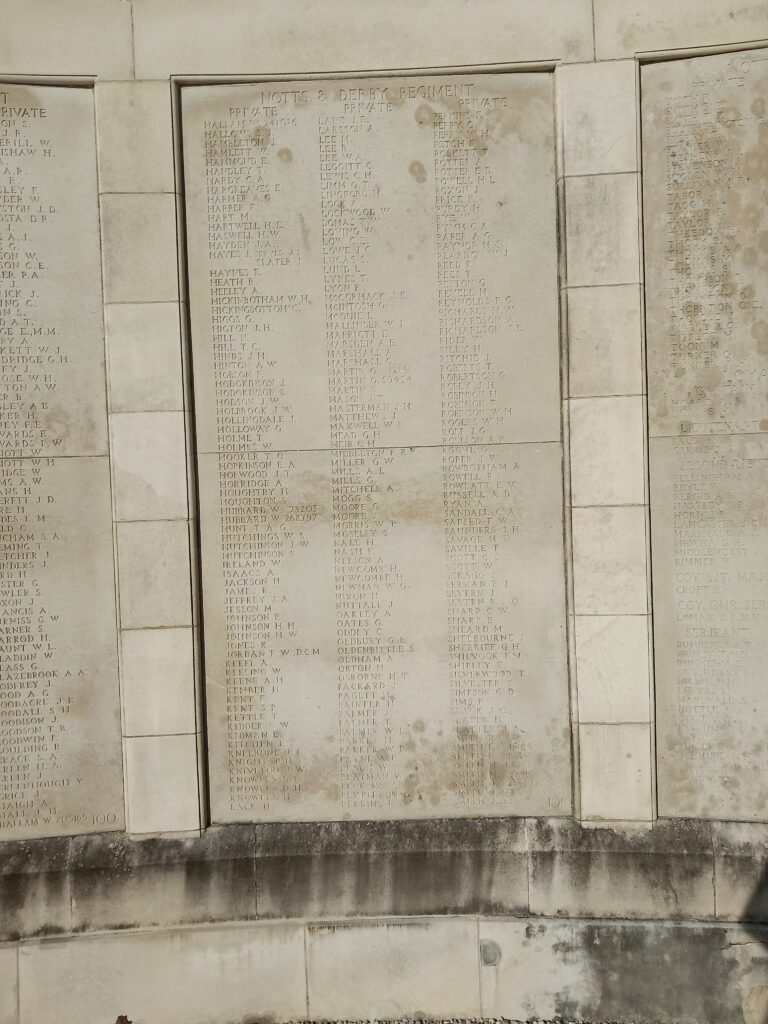

Private William Edward Benbow of the 1st/5th Battalion Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment.

Died of wounds on 1 August 1915. Buried in Lijssentoek Military Cemetery.

Lijssentoek Military Cemetry is a large cemetery located near Poperinghe, this area had 4 large casualty clearing stations. it is likely that William was injured on the front at Ypres and then evacuated back to one of the Medical clearing stations/ field hospitals.

Sapper Thomas Baldwin, 254th Tunnelling Company Royal Engineers (originally with the Lincolnshire regiment)

Killed in Action on the 22nd October 1917, buried in Poperinghe New Military Cemetery.

As a Sapper with a tunnelling Company I’ll do some investigation to try and find what may have happened at the time of Thomas’s death, it may be possible to identify from the unit War Diaries the what was going on.

Private John Bennett, 1st/4th Battalion Leicestershire Regiment

Died of Wounds 4 October 1918. Buried in Cabaret-Rouge British Cemetery, Souchez

This cemetery is north west of Arras and not far from the Vimy Ridge Memorial. it’s really well laid out and really worth the visit. I’d be interested to know what happened to John and it may well be something that I come back to look at further down the line.

Private John (Jack) Eaton, 6th Battalion King’s Shropshire Light Infantry

Died of Wounds 28th Jun 1918, Buried in Neuf-Brisach Communal Cemetery Extension.

The cemetery is located to the south of Strasbourg and the military extension contains the graves of 35 Commonwealth servicemen of the First World War, all of whom died in 1918 as prisoners of war. Unfortunately I currently don’t have the details of when John was captured or the details of his wounds.

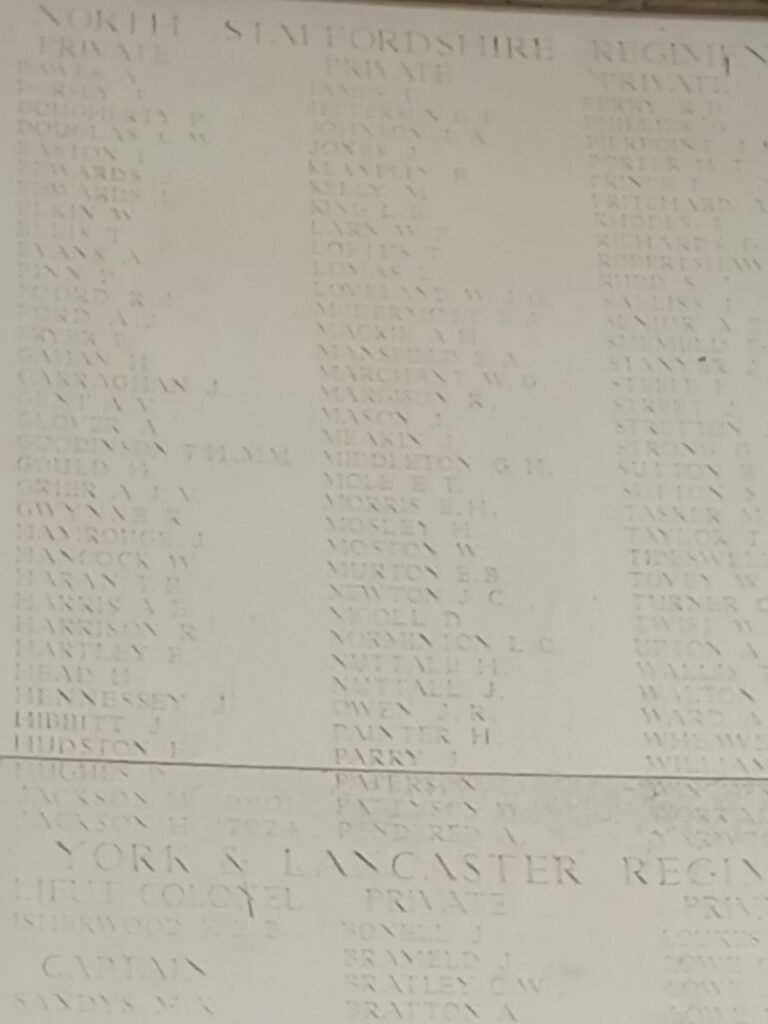

Private John William Gilbert, 8th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment

Died of Wounds 31st July 1917, buried in Perth Cemetery (China Wall), Ypres.

The Third battle of Ypres started on the 31st July and in particular the Battle of Pilckem Ridge started on that day. the 8th Battalion were part of the units taking part in the battles and it is likely that Jack sustained his injuries in these battles.

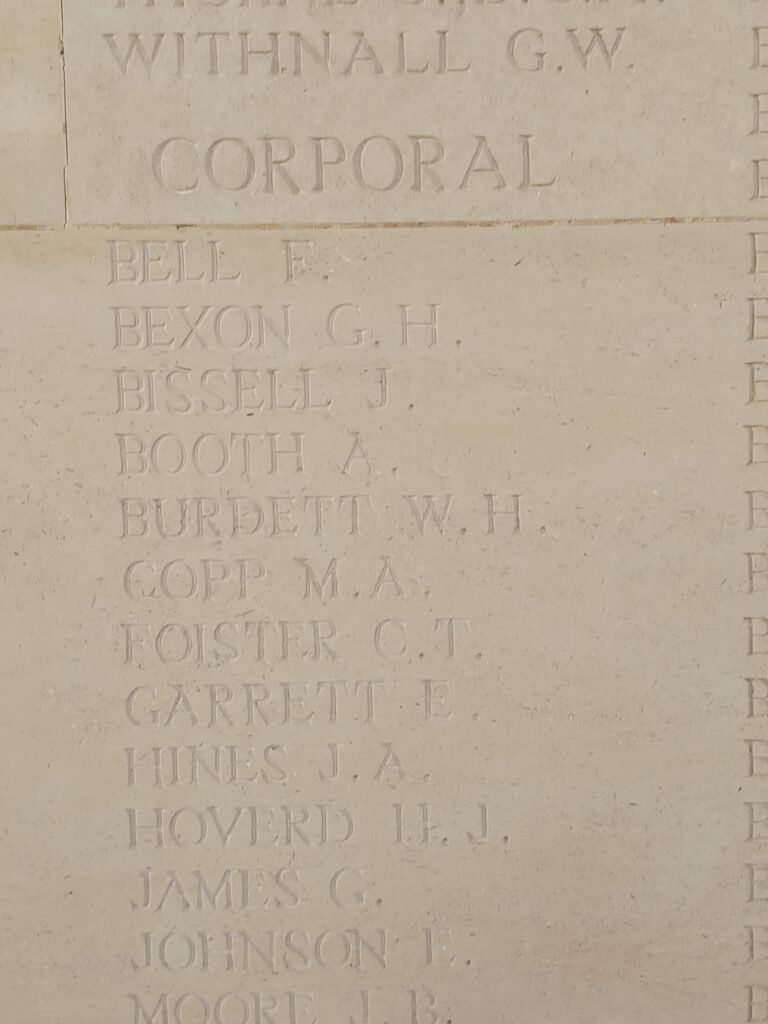

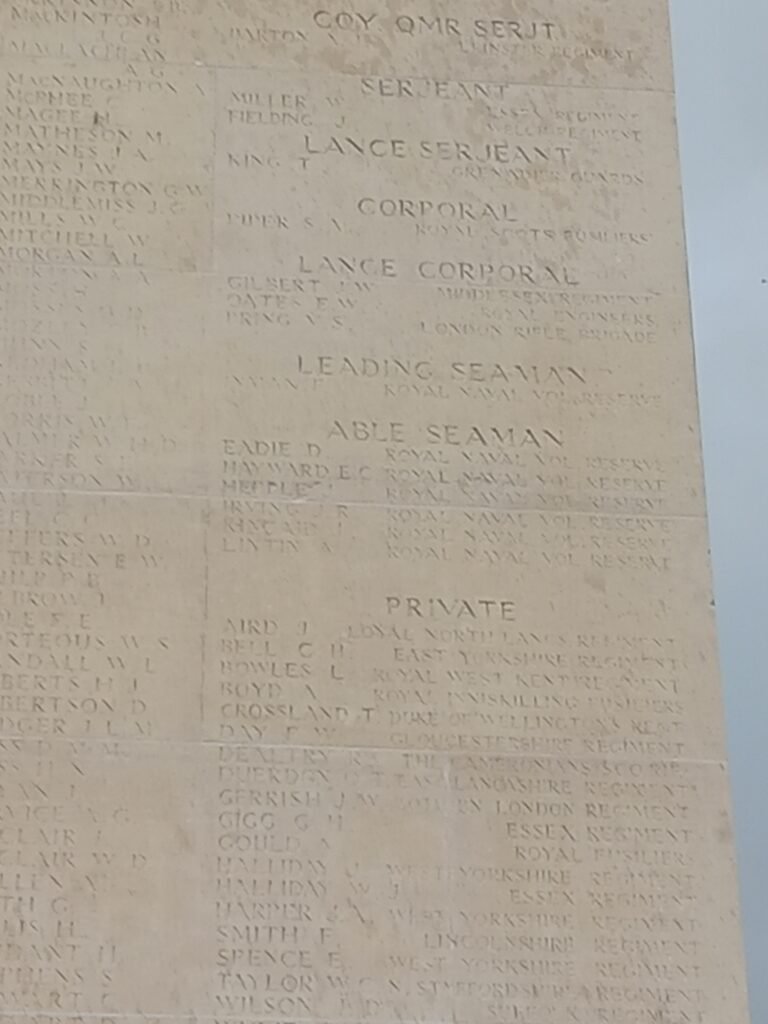

Corporal Albert Booth, 1st/5th Battalion Leicestershire Regiment

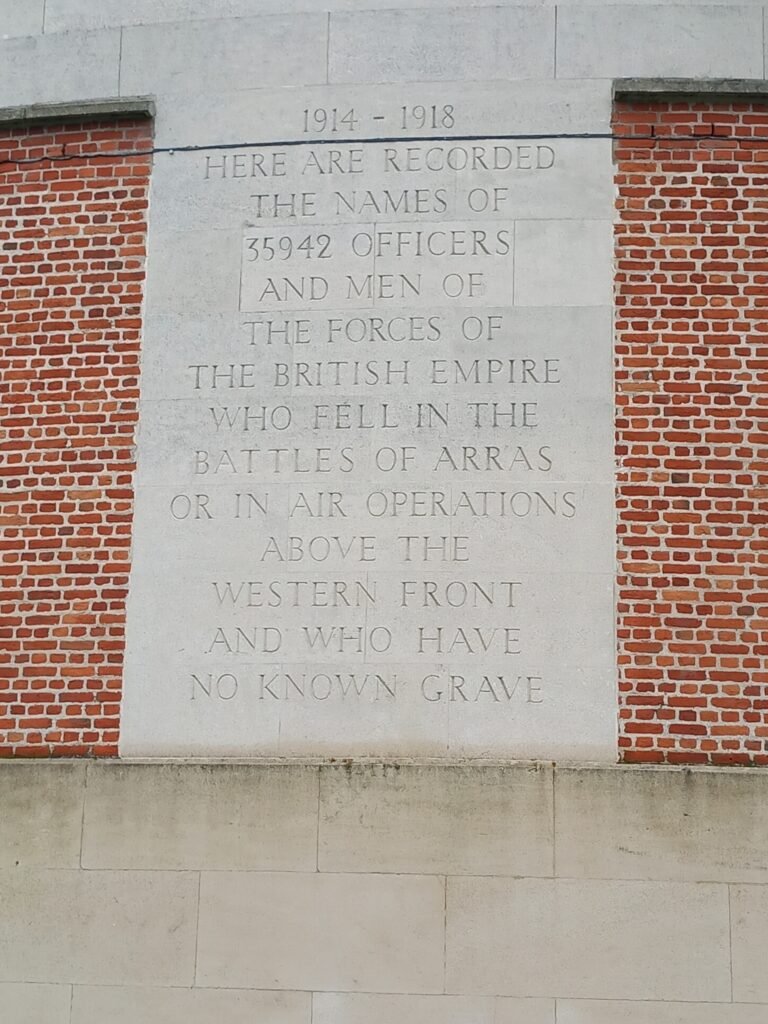

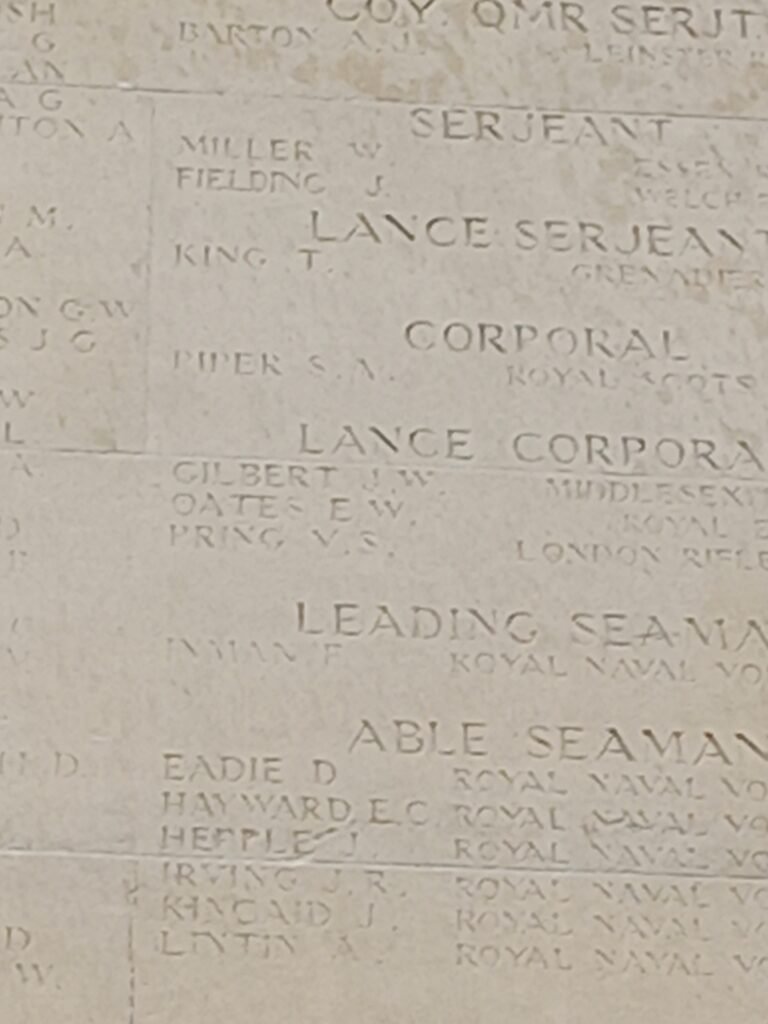

Killed in Action 8 June 1917. Commemorated on the Arras memorial

Private James Blood, 10th Battalion Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment.

Killed in Action 4 March 1917, Commemorated on the Thiepval memorial.

Sapper Frederick Brazier, 180th Tunnelling Company Royal Engineers.

Died of Wounds 30 March 1919, Buried in Hartshorne (St Peters) Churchyard, Derbyshire.

Sapper Fred Brazier was transfered to the Royal Engineers from the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment due to his civilian experience working in the coal mines at Swadlincote. In March 1918 he and the others of 180th Tunnelling company found themselves on the surface fighting as infantry trying to stop the German offensive. During those battles the Germans used Gas and Fred wasn’t quick enough to get his mask on and as a result he was badly effected by the gas.

As a result he was treated but evacuate back to England for treatment. he was eventually invalided out of the Army in late 1918 and returned home to Hartshorne. He did try and return to work in the mines but continued to have difficulty with breathing, eventually he succumbed to the damage to his lungs and died in March 19, a year after being Gassed. As his death was attributed to injuries from service he is buried with a Military Headstone.

Private Richard Buxton, 1st Battalion Leicestershire Regiment.

Killed in Action 22 March 1918, Commemorated on the Arras Memorial.

Apologies for the poor image but with the weather and the angle that I had for taking the photo it is a poor effort, the next time I’m down there I’ll go in and take a better photo.

Guardsman Willie Canner, 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards.

Died of Wounds 1st October 1916, Buried in Bac du Sud British Cemetery, Bailleulval.

This is a small but interesting cemetery and there are several Grenadier Guards buried here, along with several Royal Engineers. It is one of those locations that makes me want to investigate further what was happening in this area at the time that Willie lost his life.

Private Walter Carver, 9th Battalion Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment.

Killed in Action 10 August 1915, Comemorated on the Helles Memorial, Turkey

This is one of the sites that I’ve not been to and I’ve not been able to find an image of the Tablet that would have Walter’s name shown. I’ll try and contact a Battlefield study that is visiting Gallipoli and ask if they can get a photo of the tablet showing his name.

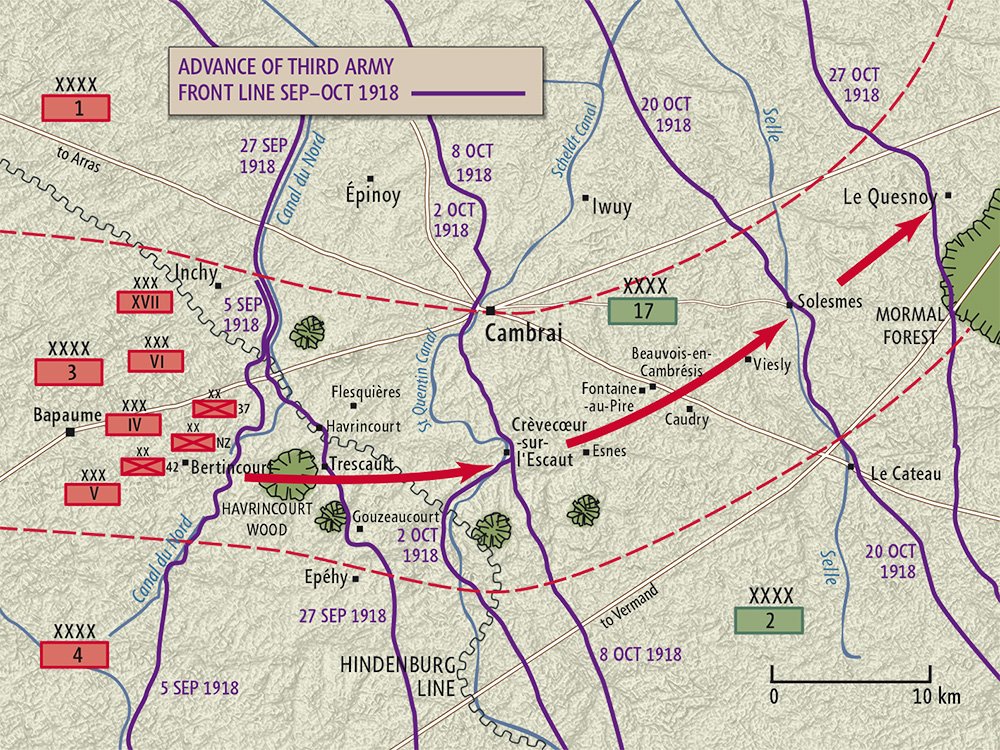

Gunner Geoffrey Gotheridge, 2nd Siege Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery

Died of Wounds 30th October 1918, Buried in Premont British Cemetery.

This cemetery is located south of the 1914 Battlefield of La Cateau, however the soldiers in this cemetery are from the offensive that helped to end the war in 1918, this was known as the last 100 days and the “Pursuit to Mons”.

Corporal James Hallam, 15th Battalion Nottingham and Derbyshire Regiment.

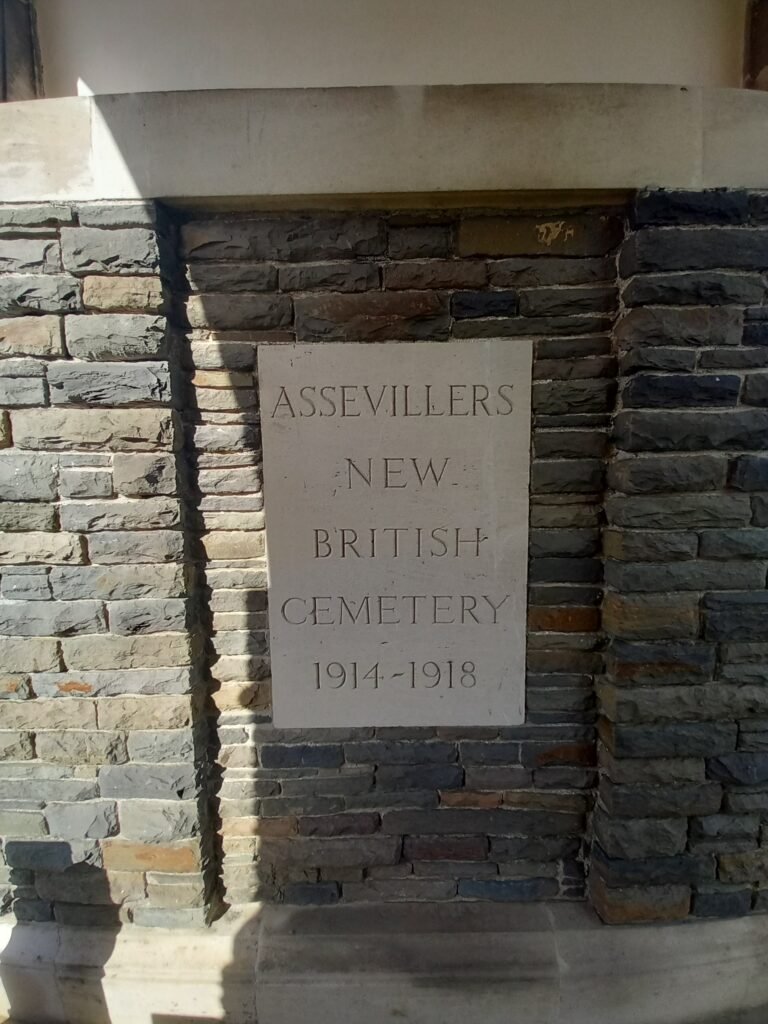

Killed in Action 28 March 1918, buried in Assevillers New British Cemetery.

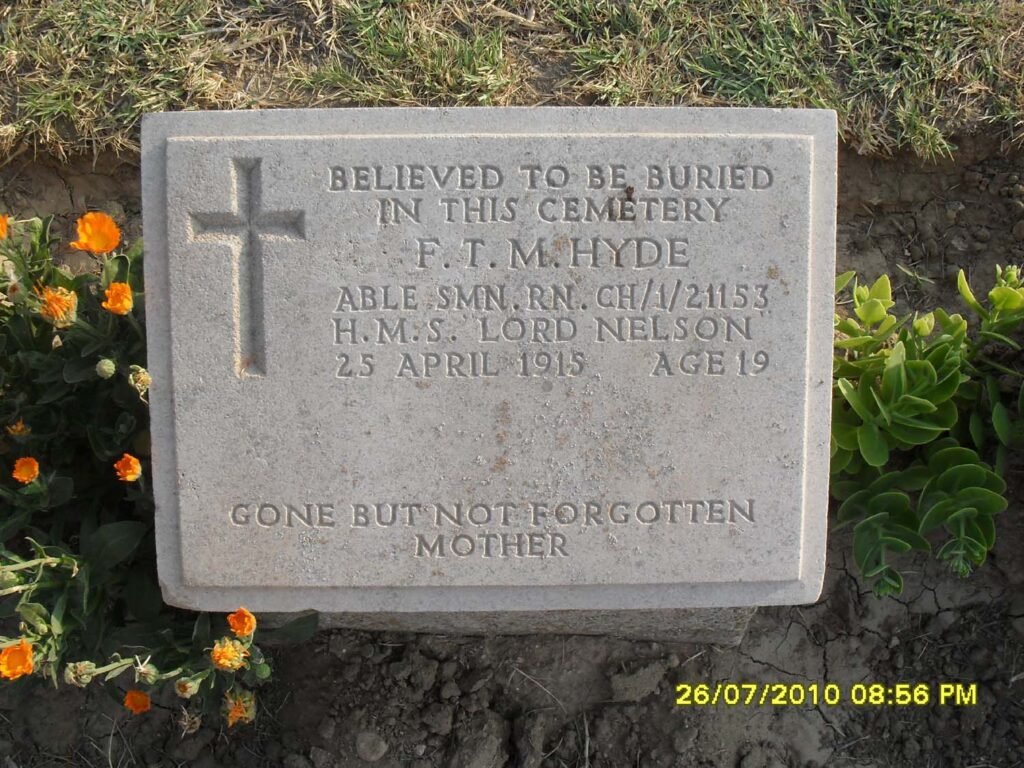

Able Seaman Frederick Hyde, HMS Lord Nelson, Royal Navy

Died 25th April 1915, Buried in V Beach Cemetery, Turkey

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56202722/frederick-thomas_mott-hyde

I haven’t been to Gallipoli but the there is a lot of information about the landings that happened on the 25th April. It appears that a detachment of sailors from HMS Lord Nelson provided the crews for the small boats that landed the infantry onto V Beach, throughout the morning. At some point Frederick was killed, but not before his bravery was noticed and he was Mentioned in Dispatches. I will definately look to do a blog post on the actions that Fred Hyde was involved in on the 25th April 1915.

Private Samuel Hyde, 9th Battalion Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment

Died of Wounds 3rd October 1916, Buried in Bourlogne Eastern Cemetery

Boulogne-sur-Mer is a large Channel port and was one of the main ports used by the British and Empire Troops. The town also had a large military hospital to deal with the wounded as well as prepapre those to be returned to England.

It is very likely that Samuel was wounded, treated at a forward aid station or field hospital and was then moved back to Boulogne to the main hospital or to be returned to hospitals in Britian but unfortunately succumbed to his wounds.

Boulogne Eastern Cemetery, one of the town cemeteries and is a large civil cemetery, split in two by a road. Unusually, the headstones are laid flat in this cemetery due to nature of the sandy soil.

At the moment this is one of the French Cemeterys that I still have to visit.

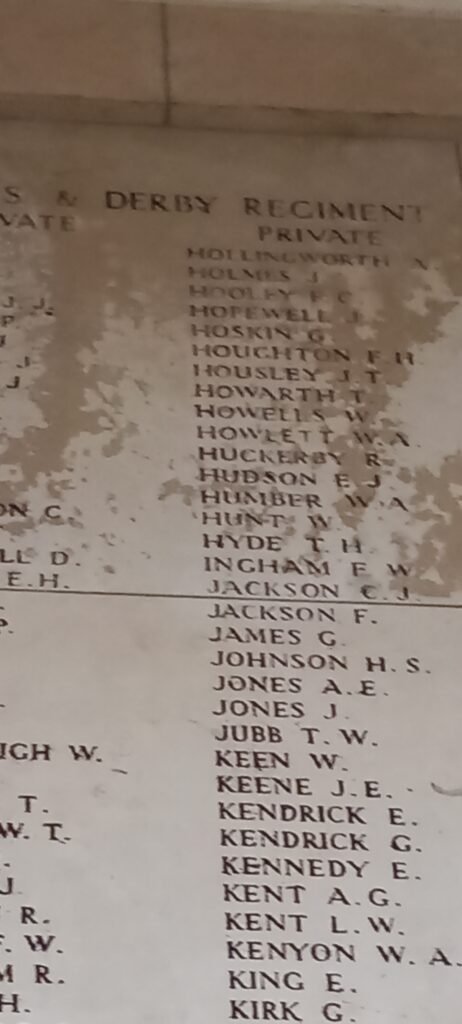

Private Tom Hyde, 10th Battalion Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment

Killed in Action, 14th February 1916. Commemorated on the Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial

Lance Sergeant Thomas King, 4th Battalion Grenadier Guards.

Killed in Action 25th September 1916. Commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial

Private Tom James, 2nd/6th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment

Killed in Action 17th April 1918, Commemorated on Ploegsteert Memorial

Not the best photograph, but Tom’s name is at the top of the centre list. At the time of Tom’s death the Battle of Lys was occurring, this was part of the German spring Offensive, Operation Georgette.

Private Frank Masters, 1st Battalion Warwickshire Regiment

Died of Infection at Ypres, 25th April 1915, Commemorated on the Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial

Unfortunately the photo that I took of Frank’s name on the memorial was too poor to add to the blog and a recent visit to Ypres unfortunately I couldn’t get another photo due to the memorial being currently being renovated. As soon at the work is complete I’ll get back to Ypres and get the image to add to this post.

Private Thomas Meakin, 10th Battalion Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment.

Died 18th September 1918, Buried Gauche Wood Cemetery, Villers-Guislain

As you look beyond the cemetery you can see the Memorial to the Indian Cavalry in the distance, which is located between Villers-Guislain and the village of Epehy.

This is a small cemetery located away from the village, Thomas was with a unit that was taking part in the Last 100 Days offensive. Villers-Guislain is located North East of the village of Epehy

Private Joseph Herbert Pegg, 6th Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment

Killed in Action 6th November 1918, buried Roisin Communal Cemetery

While this is a civilian cemetery it does have this single line of military graves, many of the men her are from the Lincolnshire Regiment, it’s hard to think that Joseph and his comrades died 5 days before the Germans surrendered and about 30 miles from the point where the war would end for the British, back at Mons.

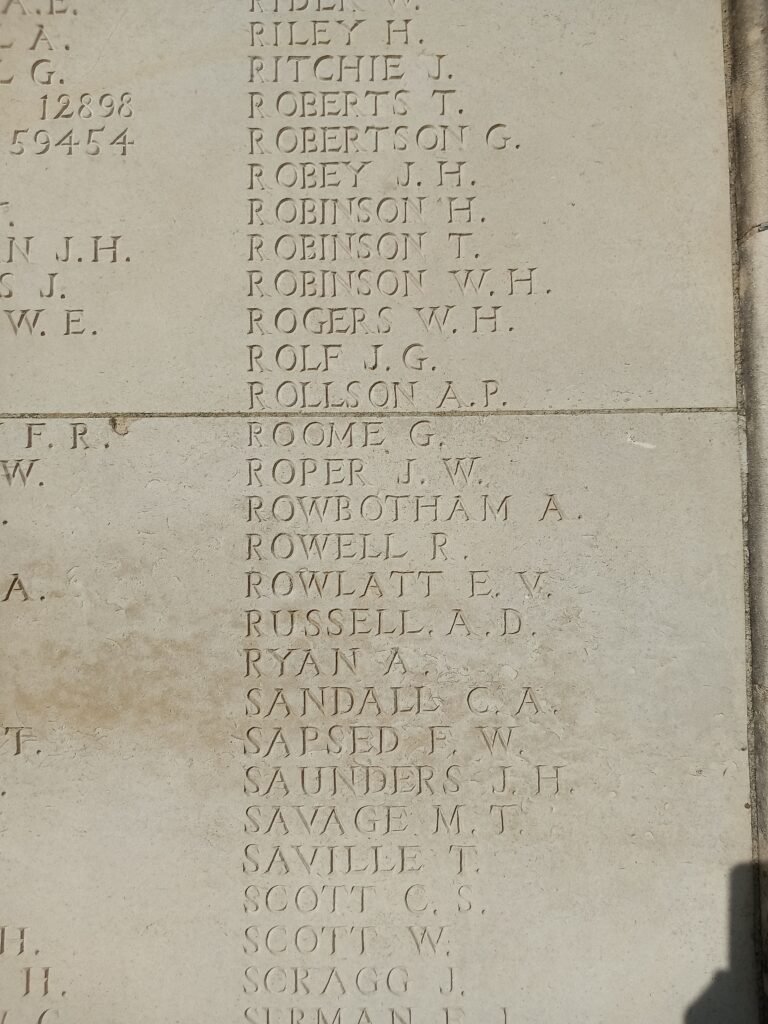

Private George Roome, 11th Battalion Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment.

Killed in Action 16th September 1917, Commemorated on the Tyne Cot Memorial

George died during the Third Battle of Ypres, also known as the Battle of Passchendaele.

WO1 Albert Sabine, Royal Engineers

Albert seems to be an interesting character, the issue is that his death isn’t until 1935 and it isn’t clear what occurred with Albert that resulted in his addition onto the village war memorial as a Great War death. More research is needed into his background.

Gunner William Smith, 19th Heavy Battery Royal Garrison Artillery

Killed in Action 12th September 1917, Buried in Canada Farm Cemetery, Ypres.

Private Samuel Staley, 6th Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment

Died of Wounds 22 August 1917, Buried in Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery

As stated for Private William Benbow, the Lijssenthoek Cemetery is located next to a number of Casualty Clearing Stations and it is highly likely that Samuel was injured during the Third Battle of Ypres and then evacuated back through the casualty system back to one of the Clearing stations or hospitals in the area of Lijssenthoek.

Gunner James Harrold Twells, 113th Siege Battery, Royal garrison Artillery

Killed in Action 28 September 1918, Buried in Ypres Reservoir Cemetery

Lance Corporal Sydney Walker, 2nd Battalion Royal Irish Regiment

Killed in action 14th July 1916. Buried in Caterpillar Valley Cemetery, Longueval.

Lance Corporal John Walton, 1st Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment

Killed in Action 1 September 1916, Commemorated on the Thiepval memorial.

Private Bailey Webster, 9th battalion South Staffordshire Regiment

Killed in Action 13 February 1916, Buried in Ration Farm Military Cemetery, La Chapelle-D’Armentieres

Sergeant Albert Webster, 5th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment

Died of Wounds 7 February 1921, Buried in Hartshorne (St Peters) Churchyard, Derbyshire.

Albert is buried in the village church cemetery and died 3 years after the war, it would be interesting to find out what the wounds were that he died of, there will be the need to do a bit more investigation on this. Albert served in the same Battalion as my wife’s grandfather who was gassed in March 1918 and suffered with breathing issues for the rest of his life, a question could be was Albert gassed at the same time? So more research needed on this one.

Private Percy Winfield, 6th Battalion Leicestershire Regiment

Died of Wounds 19th July 1916, Buried in Heilly Station Cemetery, Mericourt-L’Abbe

Looking across Heilly Station Cemetery Heilly Station Cemetery is interesting as the vast majority of the graves are double or triple burials, most of whom are from the summer of 1916, which suggests that this was near or next to a field Hospital. This is supported by the fact that is it quite a distance back from the front lines of mid to late 1916.

Addition

The following soldier is not a Man of Hartshorne but his connection to the village is that he was the brother of Mr JT Alsop of the Scaddaws, Hartshorne.:

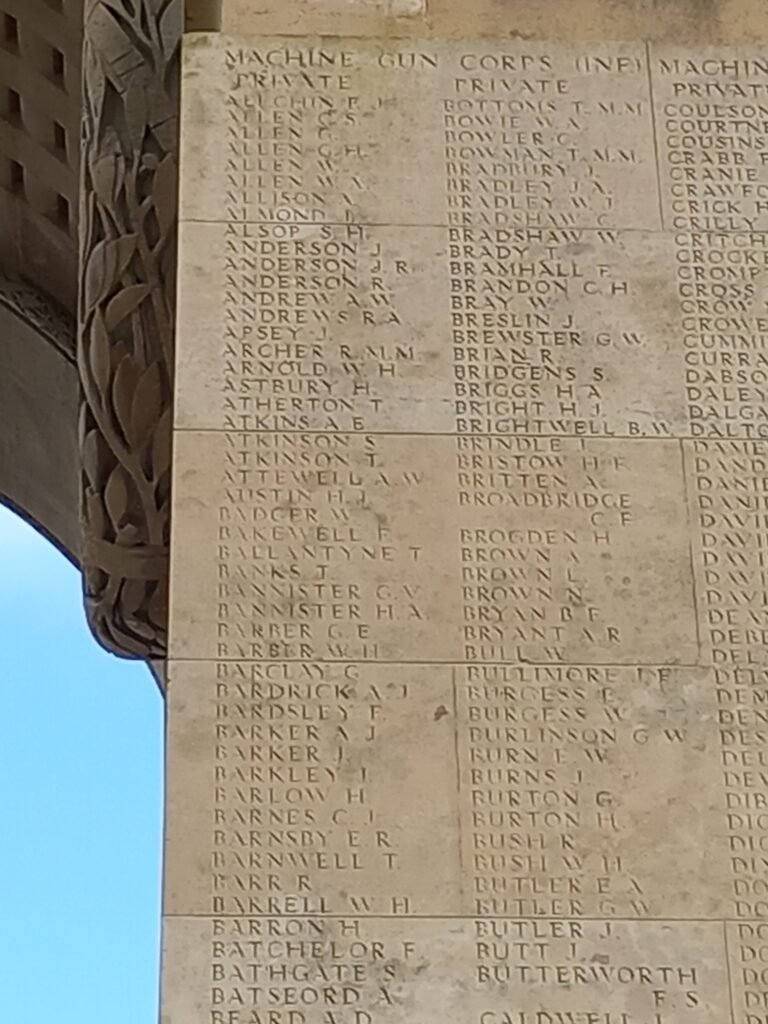

Private Samuel Alsop, 13th Company Machine Gun Corps.

Killed in Action 13th September 1916, Commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial.

Updates from the Horseback Sapper

Hello Everyone, you may have noticed some changes to the website, this has been due to changing the website host and also the layout. The new hosting plan now works better for how I use the website and for what I want to do with it going forward.

I’ve also been busy recently with tracking down some more of the Men named on the village war memorial, this will probably require a couple of separate posts, such as those in the Ypres area and those in the Arras and Amiens area.

Also there will be an update on the next stage of progress on the 1890 Saddle.

There are also a number of events that I’ll be attending this year, the first of these will be at the RE Museum in early April, this will be used as practice as we have been invited back to the “We Have WaysFest 5” which is in July.

So there is a lot planned, and also there will be continued adjustments on the website, please feel free to give some feed back on the layout and style of the pages and post. That way I can look at adjusting where I can.

Right then, time to finish my brew and get on with mucking out the nags.

Meeting the need for water in the 1917 Desert Campaign

I’ve always been interested in the Campaigns in the Middle East, probably due to films such as “Gallipoli” and “The Light Horsemen”. When I started to really dig into the RE Mounted History an area that does offer a lot of information is the Campaigns in Palestine and Mesopotamia. While I am about to finish an post on the engineer work put in place for the attack at Beersheba on the 31 Oct 1917 as part of the 3rd Battle of Gaza, I have been distracted by current Middle East events in the Gaza area.

The thing that has created the distraction is the media cries that water has been cut to Gaza and that the locals don’t have access to water.

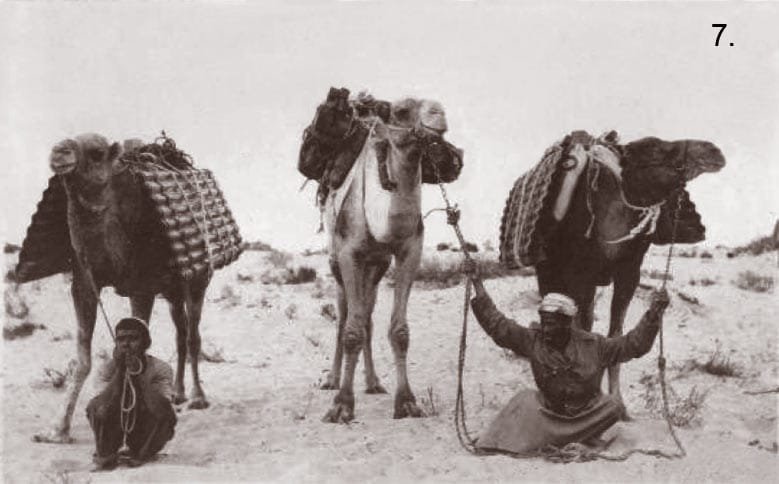

THE BRITISH ARMY IN THE SINAI AND PALESTINE CAMPAIGN, 1915-1918 (Q 12704) Australian Light Horsemen, Australian and New Zealand Mounted Division, watering their horses at Ain es Sultan (Elisha’s Well). Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205067316 I’m not going into the politics or side taking, those are discussions that can take place else where away from this history blog. I want to consider the facts that the British and Imperial Forces fought the Ottomans over this very ground in 1917 over three battles. In this theatre, water is a key requirement because without it you cannot fight, particularly in the period of the Great War. There are three key users of water in this type of warfare:

- Men

- Horses, Mules, Camels and Donkeys.

- Train Engines.

The Ottomans held the wells at Gaza and also the significant wells at Beersheba off to the east (the end of the Ottoman Defensive Line). What existed south of this point were considered as minor wells and were used by the Bedouin Arabs that lived and migrated in the area.

To meet the water requirements for the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) there would be a need to supply water either from existing supply and sources back in Egypt or to create/ exploit water sources locally.

The Royal Engineers could meet the requirements of both options.

A pipeline was created to push water forward across the Sinai, following a coastal route, from the Nile and would be added to as the EEF advanced. Also all of the EEF Sapper units would have water development and water supply as one of their key roles in the campaign.

The Egyptian pipeline under construction with RE Works supervision and Egyptan Labour Corps personnel By January 1917 the British and Imperial Forces of the EEF had crossed the Sinai and were established at El Arish and were raiding Rafah (9 Jan 1917) to the north. At El Arish the pipeline from the Nile had arrived and was providing 230,000 gallons of pumped water per day.

By March 1917 the EEF had pushed forward to south of the town of Gaza. As they moved forward the sappers worked to repair and develop sources of water at a local level.

- On the 12th March 410 and 412 Field Companies RE moved to Rafah and developed the water supply in the local area, good quality water was found in the Sand Dunes near the sea and many tube wells were sunk and all provided good yields. 412 Fd Coy RE and support from the Egyptian Labour Corps troops errected 100,000 gallon water storage in this area.

- North of Rafah at Khan Yunis, 437 Fd Coy RE repaired the the well and the pumping plant to bring it back on line.

- By 21 March, in the Khan Yunis area 439 Fd Coy ARE had sank wells to provide a yield of 100,000 gallons per day.

- Further deep wells were developed at Khan Yunis between the town and the coast to provide 130,000 gallons per day.

Norton Well Driving apparatus could be used to drive both shallow and deep wells – ground conditions dependant

THE BRITISH ARMY IN THE SINAI AND PALESTINE CAMPAIGN, 1915-1918 (Q 12622) Royal Engineer’s pumping water from the subterranean fountain from which Solomon’s Pools reserve are fed. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205067244 The EEF had created their front line north of the town of Deir El Balah. In this area the RE units had created several shallow wells which were giving very good yields. It was also found that the area of Wadi Ghazzee which ran from the coast, just north of Deir El Balah, and headed East/South East into the Desert offered good potential and as such would allow the EEF to widen it’s front against the Ottomans and not to be constrained to the narrow coastal strip.

When exploring the Wadi Ghazzee area it was found that there was large supplies of water, this was particularly the case towards Shellal, which had natural springs.

A large part of the water used for the 1st and 2nd battles of Gaza (March and April 1917) were provided from these sources and also from the pumped pipeline from El Arish. It should also be noted that even once wells were developed work did not stop on them, improvement works were constantly happening and it was noted that the deep well at Khan Yunis had been improved to produce 168,000 gallons per day by the 27th March 1917 (the second day of the 1st battle of Gaza).

Working hand in hand with the water supply was the pushing forward of the rail network, which had been pushed forward to Deir El Balah. this allowed troops, stores and supplies to be moved forward, part of this was water supplies from the end point of the Nile Water Pipe at El Arish. Water storage was created at the rail head to store this train shipped water. The wells in the Deir El Balah area were connected to pumping system at the rail head and this allowed for water to be pumped to a water storage area near Khan Umm Jerra in Wadi Ghazzee. This storage area provided 90,000 gallons of stored water and water points for 300 Camels and 300 horses at a time, this was all in a location that could not be observed by the Ottomans.

THE BRITISH ARMY IN THE SINAI AND PALESTINE CAMPAIGN, 1915-1918 (Q 12873) Members of The Royal Engineers and the Egyptian Labour Corps restoring wells and cisterns at Beitin (Bethel), which was captured by the 180th Brigade, 60th Division, on the 29th December 1917. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205248126 After the close of the 1st battle of Gaza, (26&27 March 17), 410th and 413th Fd Coy REs move into Wadi Ghazzee and sink 21 wells in the gravel areas, while the majority are shallow wells some go as deep as 60 feet, these wells end up providing 40,000 gallons per day. These field Companies are then joined by the Sappers from 54th Infantry Division who create more wells in the Wadi Ghazzee and also clean and repair old water cisterns, these additions provide 70,000 gallons daily

THE BRITISH ARMY IN THE SINAI AND PALESTINE CAMPAIGN, 1915-1918 (Q 12881) Members of The Royal Engineers and the Egyptian Labour Corps restoring wells and cisterns at Beitin (Bethel), which was captured by the 180th Brigade, 60th Division, on the 29th December 1917. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205248134 The 2nd Battle of Gaza occurs on the 17-19 April and while it is more successful than the first battle it does not dislodge the Ottomans from Gaza so work must continue to support the troops holding the area in preparation for the future actions.

In May 1917 the deep wells at Khan Yunis were upgraded with pumping plants, this allowed production to increase, for one of the deep wells on its own the production increased to 80,000 gallons per day. On the 11 May the 220th Army Troops RE started work on a 250,000 gallon Water Reservoir in the Khan Yunis area.

Gwynnes’ Portable Pumping Set – Capacity 6000 gallons per hour

Aster- Gwynnes’ Pump set mounted on wheels By the end of May work continued to create new wells in the Wadi Ghazzee area, these added a further 120,000 gallons and had pipes laid to forward water dumps, complete with concrete water tanks and sunshades.

THE BRITISH ARMY IN THE SINAI AND PALESTINE CAMPAIGN, 1915-1918 (Q 12881) Members of The Royal Engineers and the Egyptian Labour Corps restoring wells and cisterns at Beitin (Bethel), which was captured by the 180th Brigade, 60th Division, on the 29th December 1917. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205248134 By this point in time the pipeline from Egypt had reached it’s final limit and was a 150 miles long and maintained a pumped pressure at all of it’s delivery points.

The gravel wells in Wadi Ghazzee were continuing to produce plenty of water but the quality was classed as Brackish but was still classed as potable (drinkable) water. The springs at Shellal had been enhanced and were providing 250,000 gallons per day, while the springs at El Qamle and Bir Esani continued to provide good yeilds (100,000 gallons per day at least per day)

On the front line sector of El Mendur (from the coast and directly across the front of Gaza town) it was found that the local wells were sufficient to supply the troops on the front, and as such the localised pipeline from Deir El Balah and the Wadi Ghazzee reservoirs.

It was recognised that there would be further actions to take Gaza and as such the Corps developed extra wells in the dunes areas at the mouth of the Wadi Ghazzee (at the coast, west of Deir El Balah), these wells would yield brackish but drinkable water of sufficient quantity to supply 2 infantry divisions as emergency supply if required.

By June 1917 220th Army Troops RE took over the Khan Yunis water area to free up RE Field Companies for front line/ forward area works. This was as part of the preparation work for what would be expected as the 3rd battle of Gaza. During June and July the water sources between Deir El Balah and Shellal were fully developed and provided with mechanical pumping plants.

Mechanical engines would often be used to power the larger pump sets at the larger yielding wells. In September 1917, the Sheikh Abbas Sector (the eastern sector in front of Gaza Town and joined the El Mendur Sector) now had deep wells yeilding 123,000 gallons per day, with having this source close to the front means that there is now reduced requirement to move water forward from Deir El Balah and Wadi Ghazzee. At the same time 410th Fd Coy RE was installing mechanical pumps on the smaller wells in this sector.

A lightweight mechanical pump found to be ideal for the smaller and shallow wells – Rotorplunge Pump and Lister Petrol Engine. The last major piece of water works in this area was the installation of a pumping plant at the deep well at the mouth of Wadi En Nukhabir (located 2 miles South West of Deir El Balah), this work was carried out by 496th Field Coy RE.

By the start of September the plan for the 3rd Battle of Gaza was being developed and the plan is to attack the far Eastern end of the Gaza defensive line at the town of Beersheeba, and as such the focus for forward areas water development and supply was to push away from the coastal area and start to develop further east into the Wadis and desert areas. This work along with the railway expansion will be covered in it’s own blog post hopefully before Christmas.

One of the developed well sites believed to be at El Baqqar out in the desert on the route to Beersheba as preperation for the 3rd battle of Gaza. So from all of the information above it is possible to see how the British and Imperial forces were able to cross the Sinai desert and take the battle to the Ottomans. Also while the pipe line from Egypt helps to sustain the force and allows it to push forward, it is key that sappers push ahead and develop the existing sources and develop significant new water sources. Once more equipment and time permitted then the new wells are improved and fitted with pumps and reservoirs.

THE BRITISH ARMY IN THE SINAI AND PALESTINE CAMPAIGN, 1915-1918 (Q 13165) Watering horses and camels outside Beersheba Station, 1st November 1917. This area was captured by the 4th Australian Light Horse Brigade on the 31st October 1917 and became the Headquarters of the Desert Mounted Corps in November. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205194793 The questions that I currently have going around in my mind in relation to the current conflict are:

- Are any of the deep and shallow wells from 100 years ago still in use? If they are what type of yields are they producing?

- Considering that the Corps was developing water extraction both in terms of shallow (30 feet) and Deep (100 feet) depth and from a variety of locations and sources, have the Palestinians developed their own set of wells and extraction points?

- There has been plenty of discussion about the use of desalination plants, but accepting that these can be expensive, but has there been any work by any of the aid agencies to look at creating more localised water extraction?

The Great War locations of Front Line, Deir El Balah, Khan Yunis and Rafah shown on a modern map og the Gaza Strip. I don’t know the answers to the above questions but it does strike me that modern conflicts forget to look back at solutions that may actually be more viable but have been forgotten due to the advance of technology. It is clear that there was good viable sources of potable water right across the area of Gaza and Sapper field units were able to exploit them quickly and once established they could be improved in infrastructure terms and this would in turn improve the yield.

I wonder what could be done by 8 people with some modern equipment, a modern version of the Norton Tube Well driving apparatus, a robust submersible pump and some modern flexible/ collapsible storage tanks. Its just a thought?

Notes and references:

1. The History of the Corps of Royal Engineers, Volume 6. (1952) Institution of Royal Engineers.

2. Lt Col EWC Sandes DSO MC RE (1937), The Royal Engineers in Egypt and the Sudan 1800-1936, The Naval & Military Press.

3. http://www.longlongtrail.co.uk – An excellent site for information on the Great War.

4. Lt DC Howell-Price (1914), The Light Horse Pocket Book, Originally published by Angus & Robertson Ltd, Reprinted in 2020 by The Kangeroo Feather Publishing Company.

5. Instruction in Military Engineering (Part 5)- Miscellaneous (1898) School of Military Engineering, Fifth Edition, War Office.

6. Military Engineering Volume 6 Water Supply (1922), His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

7. David Murphy (2008), The Arab Revolt 1916-18, Osprey Publishing

8. Mike Chappell (2005), The British Army in World War 1 (3) – The Eastern Fronts, Osprey Publishing

The Royal Engineer that improved Water Supply in the Middle East

In the Great War the biggest challenge facing operations in the Palestine Theatre of operations was to try and to provide water to the troops and 1916 saw the troops of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force push out into the Sinai Desert with the aim of taking the fight to the Ottomans. However to fight in the desert, one of the essential logistic items is that of water. Without sufficient water the range of operations would always be severely limited.

Therefore there was a need to develop existing wells to increase production and also to create new wells. The Royal Engineers had equipment to create wells but the difficulty was to develop equipment that could be more portable to allow the provision of water as the troops advanced, as well as having the ability to produce water in an appropriate quantity.

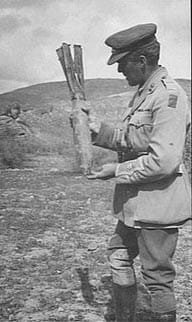

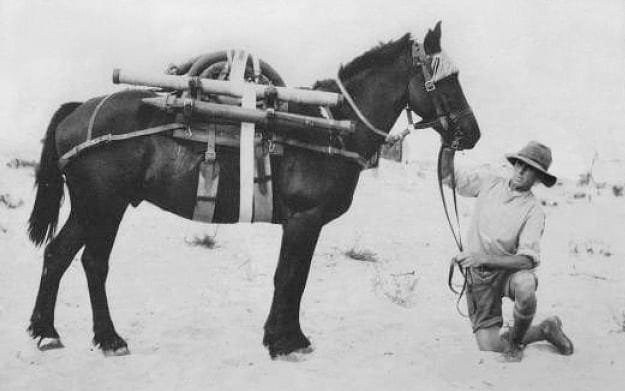

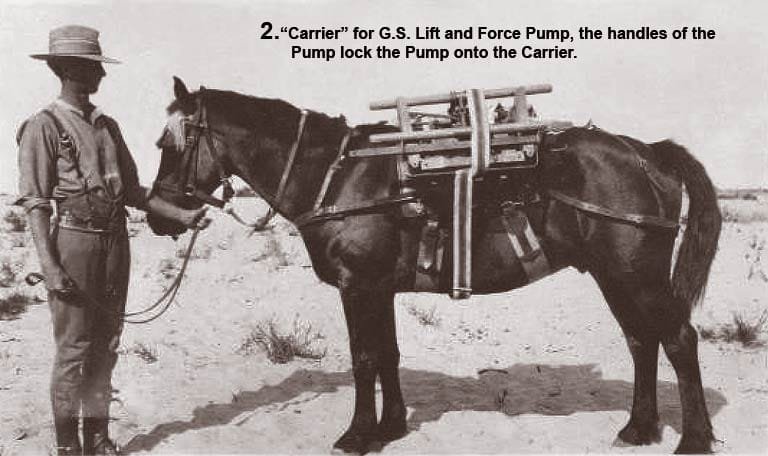

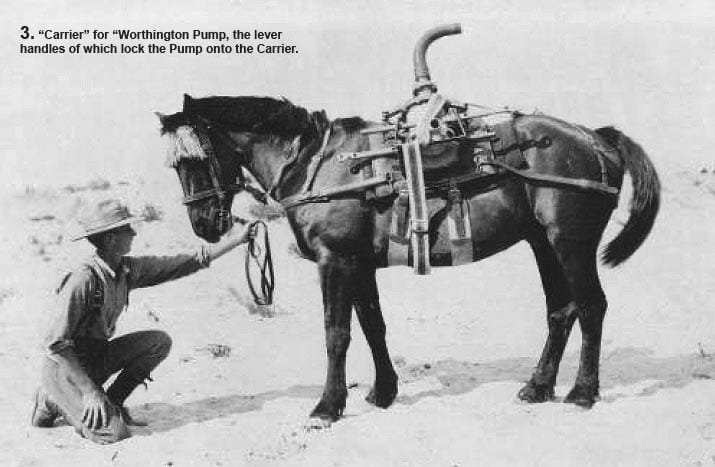

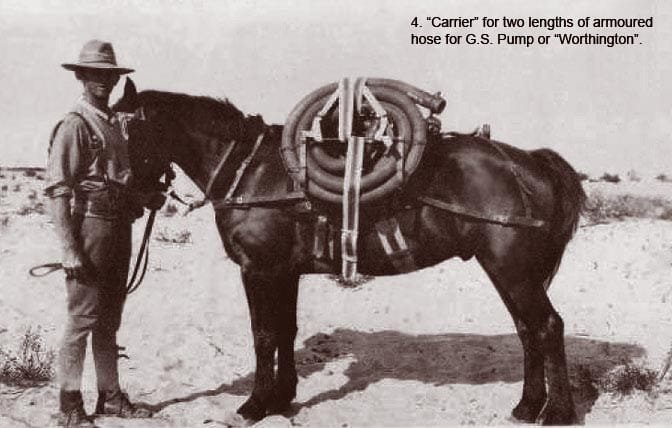

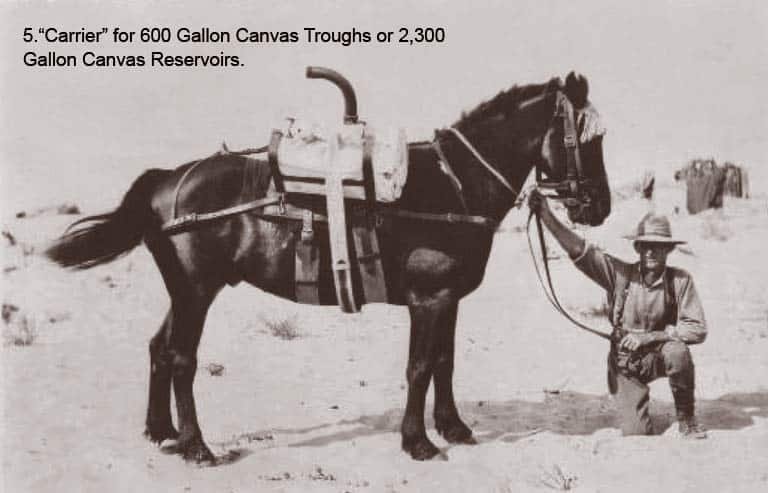

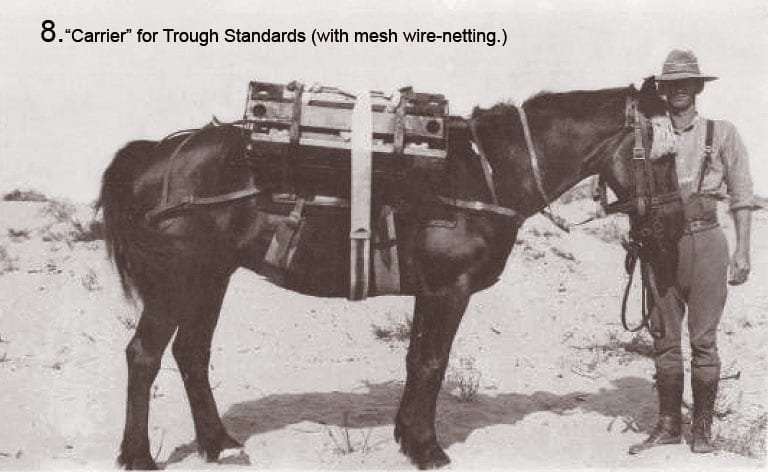

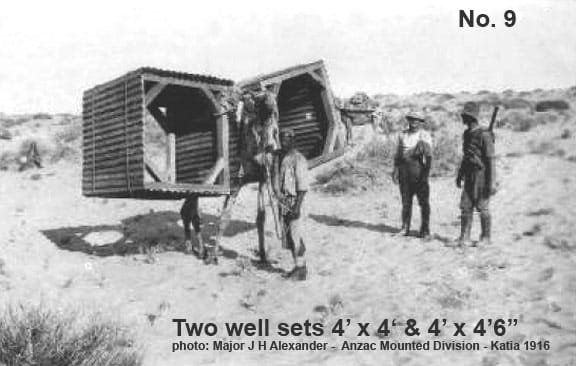

What appears to be a shallow well with a lift and force pump A Royal Engineer attached to the ANZAC Mounted Division, in 1916 developed a more portable system of equipment that could be carried by horses and deployed quickly by a Royal Engineer Mounted Troop. The officer was Major Alexander RE.

Maj Alexander RE in 1918 examining a Turkish “Air torpedo” Major Alexander looked at the existing deployable equipment and realised that a large amount of it was transported by Camel, while this allowed it to get out to the remote areas that it was required in, it was too slow and certainly could not keep up with the Mounted Divisions during operations, as such the camel mounted system was better suited for follow on operations. What was needed was a lighter system.

It became clear to Major Alexander that the whole system had to be modified to be fitted on pack horses, this would allow the equipment to be utilised by the RE Field Troops attached to the Mounted Brigades and still keep up with them as they moved.

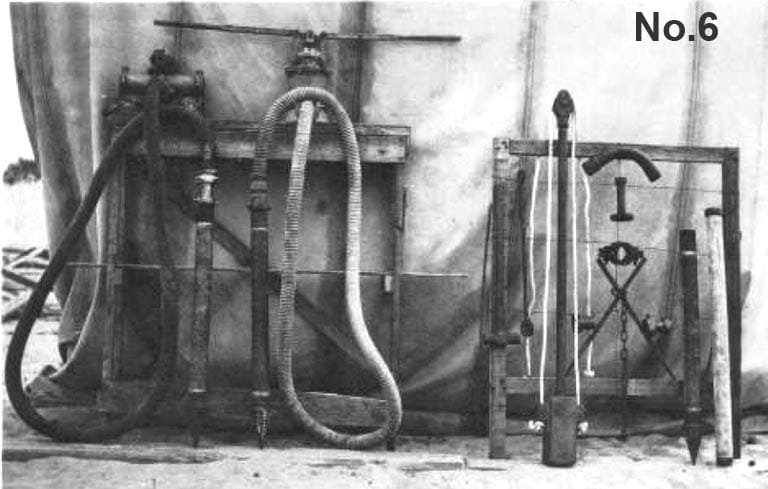

His system developed what was known as a Spear tip for the driving head of the pipe that would be sunk into the ground – this appears to be very similar to what the Sappers of my era would recognise as the driving head for a Camoflet – the Spear Tip method was already used in rural Australia but by looking at the whole water supply requirement he brought together a full system that would be portable by pack horse/ mule.

The well pipe would be driven in using a drop weight system or if necessary it could be hammered in by Sappers themselves using sledge hammers.

While the lift and force pump was the main pump set used by the Royal Engineer Field Troop and Squadrons they would not be sufficient to raise the quantity of water needed to sustain units in the desert, so he looked at existing pump sets. He found that the Lister and Worthington Pumps were light enough to be carried on pack saddles but also powerful enough to pump water from both the shallow and deep wells. The Royal Engineers defined wells into 2 categories – shallow (40 feet deep) and Deep (100 feet deep).

Image shows the drop hammer and also driving heads.

Authors Note -While this may be a light weight construction, I would suggest that this is pushing it a bit as a load for the horse! I think it would have been better for the pack horses to have these collapsed into more manageable loads!

The key is to get the load balanced. Having looked at all of these photos it does appear that all of the loads are fitted to the standard General Service Pack Saddle with only slight additional modifications such as additional straps and extra surcingles. Also the loads – with the exception of the Well Set load – all look very manageable and balanced.

While his developments and creation were put in place for the Sinai campaigns in 1916, they would proved invaluable for the campaigns at Gaza and Beersheba in 1917 and would become essential equipment of the Royal Engineer Field Troops attached to all of the Mounted units of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force.

Authors Note – I first came across Major Alexander RE and his work in 2016 when researching the work of the RE mounted Troops in the wider Middle East. I came across a New Zealand Website which gave the details of Maj Alexander’s background being of Irish and New Zealand extraction. The majority of the images of the pack horse loads are from that website, unfortunately the website no longer seems to be available as I would like to give credit to that site as it provided a big chunk of the information that I used in my original facebook post on this topic and provided the basis for this blog post.

If anyone knows if the New Zealand website has moved to a new address then please let me know as I would like to provide a link to it and to give it the credit for setting me off in the right direction with this research. Regards Will Mac

Remembrance Day at Maisieres

This morning I represented the British Forces at the Church at Maisieres at Mons. This is the local church to where I live out here in Belgium and I volunteer to lay the wreaths here due to the Royal Engineers connection of the village and the church.

At the Church there is a memorial plaque that commemorates the British units that defended the section of the Nimy Canal on 23 August 1914.

56 Field Company Royal Engineers are named on the Plaque and as such I feel it is my responsibility to attend this location on behalf of SHAPE and the Corps.

Why? well 56 Field Company RE were tasked with the demolition of the 4 bridges in this area and were the first RE unit to be engaged by the Germans, they also sustained the first Royal Engineer Casualty from enemy action of the Great War – 2Lt HW Holt RE.

Holt and the other dead from the Engineers, Royal Fusiliers, Royal Irish and the Middlesex Regiment were originally buried in Maisieres before being moved to the combined British and German cemetery at St Symphorien on the eastern side of Mons.

The thing that struck me was the passion that the locals have to remember those that fought in 1914-18.

With a wreath laid at the Church memorial we all moved up to the village war memorial for a small ceremony where the names on the memorial are read out and Wreaths are laid. The move up to and back from the village war memorial had us escorted by 2 Horses and riders. From all accounts this is a local tradition and possibly dates back to just after the Great War when there was a Belgian Cavalry unit based at the Barracks that now form part of SHAPE.

So with wreaths laid it was Duty done and respects paid, it was a honour to do this morning.