Line of Communication Engineering Talk

Last weekend I had the privilege of delivering a talk at the Royal Engineers Reserves Study Weekend. This was focused on the Royal Engineer units involved in the Line of Communications.

The aim was to focus and discuss some of wide range of units used for the operation and maintenance of the Line of Communication – Basically the supply and logistics lines that supported the Front line units and the battle area.

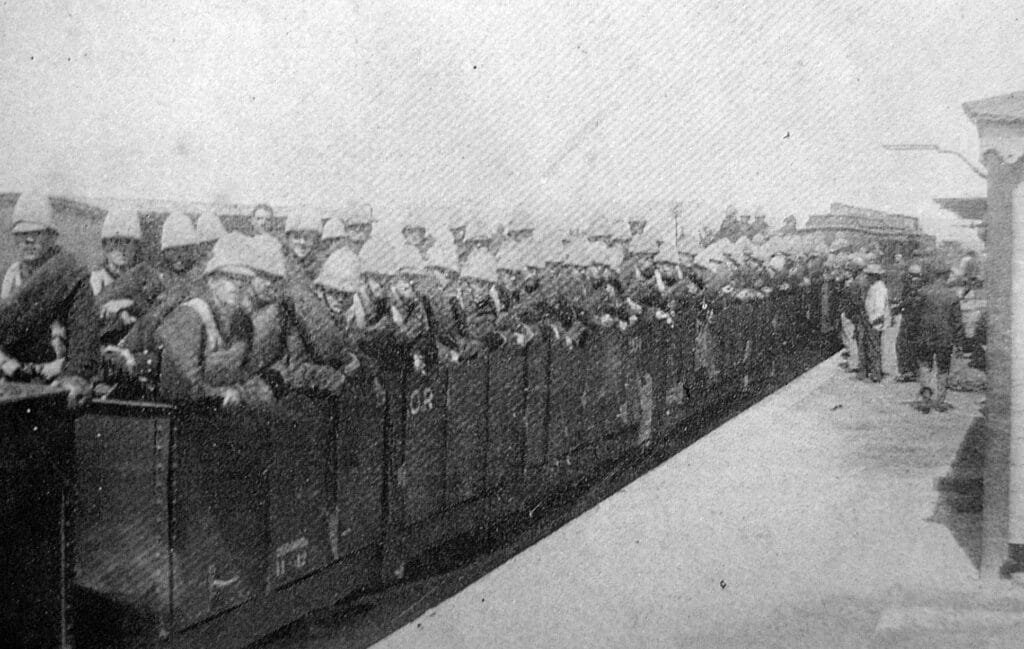

The initial part looked at how the British Army learned the lessons of maintaining and securing the Lines of Communication during the Colonial period and then how the Royal Engineers deployed and refined its many skills in the Boer war with the LoC works and units

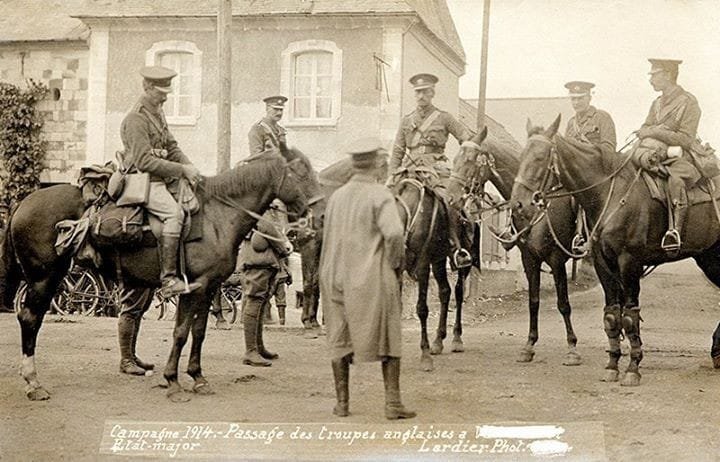

The period between the Boer War and the Great War saw some significant changes for the British army and for the Royal Engineers, with the creation of the British Expeditionary Force of 6 Infantry Divisions and one Cavalry Division. Linked with that there was the supporting RE units that were created to support the BEF and its Line of Communication.

at the start of the war the BEF had 2 Regular and 3 Special Reserve Railway companies. However the interesting part of the research was finding out that there had been very high level secret discussions between the British and French General staff in 1911 about the possibilities of a European war and how the BEF could be integrated and supported by the French. While the French made promises to support the BEF and to carry out all works and maintenance on the LoC for the BEF, in private they were quite dismissive of the fact that the BEF would only be 6 Divisions and as such didn’t merit any real support in comparison to the French Army.

Based on the assurances given, the British planning for a future European war didn’t focus on the LoC, this lack of planning and developing of organic British units would have significant impact when the war starts in 1914 and the race to catch up, combined with the rapid expansion of the British Army as a whole meant that it wouldn’t be until late in 1916 by the time that the British army had a handle on the LoC operation and the development of it going forward.

The BEF needed to provide specialist into French Ports to manage and unload the mass increase in British and Empire supply shipping It became apparent very early that the French Authorities at the British allocated ports could not deal with the increase in shipping and the management of stores, Troops and horses being unloaded and moved forward. The British had to bring in Managers and man power from British ports to take over the areas allocated and to unload shipping as quickly and efficiently as possible.

These ports also provided the locations for the RE Base Park Companies who would deal with works and stores and prepare to move items forward to the Advanced Park Companies who would then along side the Forward supply depots look at distributing the stores, material and equipment needed .

Engineer Stores being collected from an Advanced Park Company Area I also looked at the specialist LoC units that the Corps deployed and some of the impact that they had. Such as the expansion and development of the RE Railway units, both in terms of construction and operating the rail network at standard gauge and then from late 1916 the construction and operation of the narrow gauge railways.

Steam pile driver constructing standard gauge railways over rivers in 1918.

Light railway being constructed I also discussed the essential work of the RE Forestry Companies and the Canadian Forestry Corps and how they helped to reduce the need for importing timber, which in 1914 and 15 was taking 65% of tonnage space on ships, that space was needed for Men, munitions, food and supplies. As such the 11 RE Forestry Companies and the Canadians helped to reduce that significantly and by 1918 were supplying monthly and average of 51,000 tonnes of cut and worked timber for use by the BEF.

Another particular favourite unit of mine that was key to the BEF was that of the Inland Water Transport, responsible for operating of the Docks (as mentioned earlier), the navigable waterways and operation of vessels on the rivers and canals of France and Belgium.

IWT barges moving troops and stores forward from the Base Ports

The IWT operated many Hospital Barges, these allowed medical staff to continue to work on the injured during a reasonable smooth journey to the rear as part of the casualty evacuation process.

IWT barges collecting quarried material delivered by a Light Railway. It was also necessary to cover some of the other major LoC RE units, such as the labour battalions and the Road Construction Companies. These units were specifically recruited from the Navvies and the road units from the British Borough and County road departments, thus ensuring that those recruited where the masters of their trade and skills.

It was a similar story with the need for working Quarries to supply materials for construction and for the construction of roads.

And vitally important in the Flanders area was the need for specialist Drainage Companies, the Corps recruited experts from the Fen District to create 2 Drainage units.

The ramping up of the Corps through the war is interesting, while there is a lot of focus on the Special Units such as Gas Units and also the Tunnellers, the less glamorous units for the LoC are vital and their stories are just as facinating once you start digging into them.

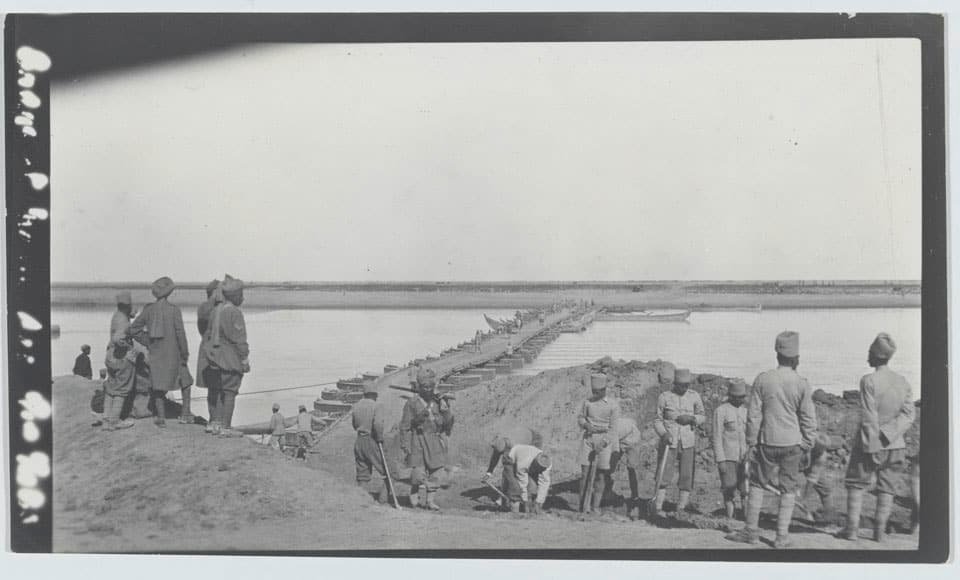

The other piece that has been interesting when researching for this talk was looking at the Line of Communication development in two other theatres that I’ve been researching over the last couple of years. In the Egypt and Palestine campaigns of the Great War the development of solid Logistics and Line of Communications were key and often dictated the pace and planning of the Operations. In contrast the lack of planning in the Mesopotamia Campaign and not establishing solid Lines of Communication in that environment impacted directly on the Campaign and many battles and resulted in a 12 month delay while the LoC problems could be fixed before serious military offensive operations could be successfully undertaken.

Egyption Labour Corps and RE Troops build a water pipeline from Egypt into Palestine during 1916 to 1917.

Troops wade through the flooded ground with their pack mules that was typical of the ground fought over regularly during the first half of the Mesopotamia campaign. Once again it has been fascinating to research the RE involvement in the LoC on the Western Front and a very specific area that I will look at in a bit more detail is the Secret talks between the British and French General Staff in 1911 to see how it impacted the early deployment of the BEF and the RE units that were deployed.

Royal Engineers Historical Society Study Day

Last week saw me in Ripon at Claro Barracks providing support for the Royal Engineer Historical Society (REHS) during their study day. The key theme was looking at Innovation in warfare and I was asked if I could put together a display of topics that was link to Great War RE Innovations.

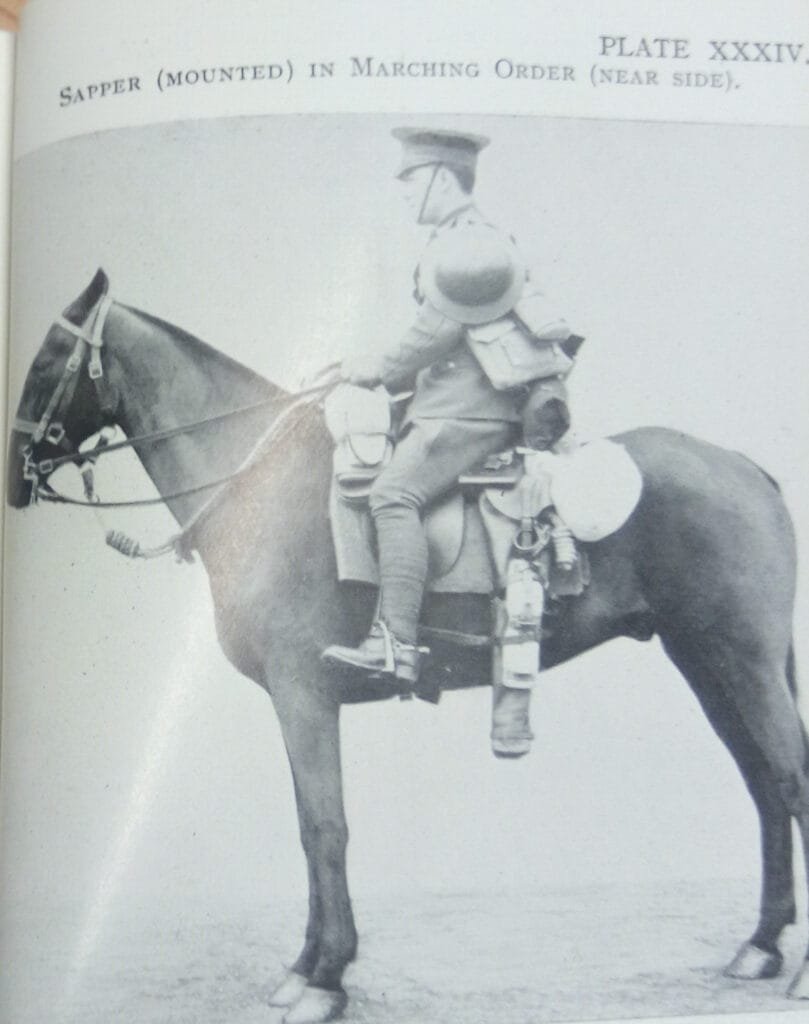

With such a vast choice of areas to choose from, I made a point of looking at items that were linked or related to the Mounted Sapper units.

The event allowed me to put on display a UP Saddle set up for a RE Field Squadron mounted Sapper.

UP Saddle with RE Tool Bucket and demolitions kit The two key elements that make the UP Saddle Royal Engineers specific are the Royal Engineers tool bucket attached to the side of the saddle opposite the Rifle Bucket and then on the rear of the saddle is a sandbag filled with 10lbs of Gun Cotton, safety fuse, primers and detonators.

These two items allowed for the Mounted Sapper to be able to carry out Combat Engineering tasks independently and when on the move. There will be more details in a separate blog post on how the RE Tool Bucket would carry tools and equipment.

The event also allowed me to set out and trial my display boards for the first time. This is worked brilliantly. Covering a set of boards with a material to allow small velcro tabs to attach means that I can change the displays quickly and easily.

The other part of the event that was a first was that it allowed me to put together my early war RE uniform. This was made possible with a jacket tailored by Matt Palmer and a early war cap made by Dickie Knight at “Khaki on Campaign”. Added to that I’ve put together a double strap Sam Browne and the Sword frog.

The engagement with the attendees was great with lots of questions on saddles and the uniforms particularly the way that engineering tools could be carried on the saddle.

The other topic that picked up a lot of focus was the innovation on the carriage of water supply equipment on Pack Horse in Palestine. Chatting with a couple of serving personnel it appears that this is a topic that is current and back in focus again so for them to see this being looked at 110 years ago was fascinating for them.

So overall a successful event, proving that the display boards and early war kit works. Now it a case of getting back into the research and prep work to get ready for the next set of events in November.

The Horseback Sapper – Going forward

This website has been a bit of an evolution over the years. It all started as a Facebook Group to help with my preparations for the Warhorse 2014 ride and then evolved to a blog/ topic research page on its own website.

Its now starting to evolve a bit more.

Having now retired from the Army I want to spend a bit more time (if the Memsahib allows and if I get all of my farm tasks completed….) doing historical research, assisting with Battlefield Studies and also taking part in more Living History events.

The research will continue to be focused on the Mounted RE Units, but I would like to dig further into the Derbyshire Yeomanry particularly as there were two troops local to where I live – Repton and Church Gresley. The infantry aspect is still of interest due to family connections with the Seaforths (my side of the family) and also with the Norths Staffords (the memsahib’s Grandfather).

Kitted out as a 5th Seaforth with the Horse Transport Platoon during a visit to Fort George The Living History side will hopefully see me providing assistance to groups such as 508 Company ASC (Horse Transport) living history group as well as linking in with other individuals.

The website is continuing to be checked as there are still blog posts that have lost their original images, this seems to have been due to a legacy issue when the blog was initially hosted on wix and then transfered over to a wordpress format. However I am now working through the old posts and updating the image archive.

There are a number of draft posts that need to be worked through and completed such as:

- RE Cable Wagon

- Correcting the Corps History – Part/ Rant 4

- Officer’s equipment

- Officer’s valise

- and several others……

Fully equipped Officers in France 1914 with field equipment and loaded saddles. The other aspect is that the website will give more information about events that I will be attending and also what I can offer if someone wants help at an event, talks, show and tells or assistance with Battlefield studies/tours or projects.

So there is a lot on the cards for the Horseback Sapper and it will be interesting going forward.

Blog Post photos – Bit of work needed!

Over the last few weeks I’ve noticed that some of the photos for the blog posts have gone missing from the posts.

So at the moment I’m working my way through some of the posts to get the images back and also set a “feature” image for each of the posts.

I don’t think there was anything sinister with the loss of the images, I think it was possibly down to the updating of the website and changing the theme/ layout. So to that end I’ve got something to keep me occupied as I check through the blog posts.

Oh well, best bash on……

Researching the Sappers in Mesopotamia

Over the last few months I have been researching the Mesopotamia campaign, 1914 through to 1918 and beyond. There is couple of things that make this an interesting focus for me. The first reason is that having served in Iraq as part of the 2003 invasion and having covered a lot of the same ground that the British covered in the Great War.

The second is while I was researching the names on a Great War memorial in Wick, in my home county, there was a Royal Engineer Officer that died in Basra in 1920. He was serving with the Inland Water Transport and died during the Arab Rebellion of 1920. All of this was interesting due to location and the fact that for some soldiers the Great War didn’t finish in 1918.

The campaign in 1914 started with some very specific aims to protect the oil supply from Persia, and the taking of Basra was key to provide the stand off for that protection. But it became very clear reading the history that the amount of politics in the background, and the unwillingness to commit resources (troops, equipment and funding) all added to a future disaster. All of this sounds so familiar to the experiences of 90 years later.

Unloading of Artillery at Basra, due to lack of port facilities local boats had to be used in the unloading process. Photo shows a Royal Engineers Field Machine, a standing derrick in use. The other aspect that became very clear of the early campaigns of 1914 and 15 was the lack of allocation of specialist troops to the operation, particularly Sappers and Gunners.

This particularly meant that there was not enough bridging equipment (tressles and pontoon equipment). The availablity of timber was so lacking locally that palm trees were considered until it was realised that they would not be able to give the appropriate level of strength required.

However, as is often the case the RE Officers and the men of the Sappers and Miners Units that were in Theatre took on the traditional mantra of “Improvise, adapt and overcome.” The metal pontoons were used singularly rather than double (while this reduced the loading it was deemed acceptable). Also some of the local fishing boats were taken into service and modified so that they could be used as pontoons in bridges.

These local craft were far from ideal but they worked and became a vital part of the Bridging equipment. They were also an important part of the ability to load and unload the larger ships/ boats that came to Basra or operated further up river on the Tigris or Euphrates.

One of the other problems was water supply. The operation was meant to be a limited action and as such there was a shortage of watersupply equipment for the Sapper Units and also of water carts for all units. With the daytime temperatures being high and the fact that the soldiers had a significant amount of marching and fighting, the 2 pints of water that they carried in their water bottles was wholly inadequate.

Sedimentation pond, part of the water supply process The interference and misreporting on the situation to meet political requirements meant that key equipment such as water supply, medical equipment and medical provision was not provided. It was only the disaster of the surrender of the 6th (Poona) Division at the Siege of Kut in April 1916 brought the Theatre into full focus and a change in the approach to fighting the campaign.

A prepared water distribution point with water being pumped into unit water carts.

Mechanical pump sets were only seen in the main locations such as Basra and Amara in the early stages of the operation, with them only progressing further into Mesopotamia later in the war (1917 onwards) Another key element that was completely inadequate in the early part of the war was the river transport, in a country where the rivers provide the best and fastest method of movement. There was a significant lack of river capable vessels, therefore it became necessary to utilise every vessels and boat that had a shallow draft.

Indian Sapper & Miners work to salvage and refloat an abandoned Turkish Army vessel With both the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers having such fluctuations in depth it was not uncommon for the vessels to runaground or to get stuck on sandbanks. As such the RE and Sapper and Miners units would often be tasked to free the vessels or assist with salvage and repairs.

Indian Sapper & Miner diver helped back to shore having been down to clear an obstruction. Later in the war it was recognised that the management of the ports and river operations needed to be significantly improved as as such the Sappers became more formally involved by the bringing into to Theatre the Inland Water Transport units and commands. This key addition of the IWT to the ports, particularly Basra, and to the operation of the rivers drastically improved the logistics across the whole of Mesopatamia.

Overall it is proving an fascinating area of research and in particular the amount of bridging carried out by all of the Sapper units and the way that they dealt with improvisation to deal with equipment shortages and also to ensure free movement on the rivers while allowing the movement of troops.

There will be more detailed and focused posts to come.

References:

Lt Colonel EWC Sandes RE, The Military Engineer in India, 1927 Naval and Military press

NS Nash, The Betrayal of an Army, Mesopotamia 1914-16, 2016 Pen and Sword Books

C Townsend, When God Made Hell, The British invasion of Mesopotamia and the creation of Iraq. 2010

Faber and Faber

Major EWC Sandes RE, In Kut and Captivity, 1919, Murry publications

1st July, The Somme Offensive – a personal take

This is a very short post but it would be remiss not to take the time and the moment to just remember that today is the 109th anniversary of the start of the battle of the Somme – 1 July 1916.

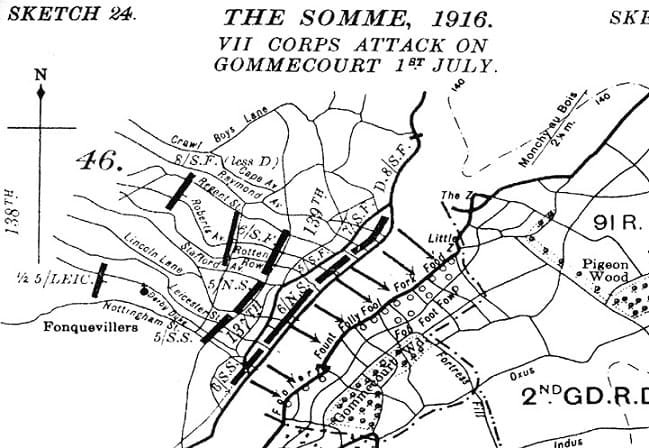

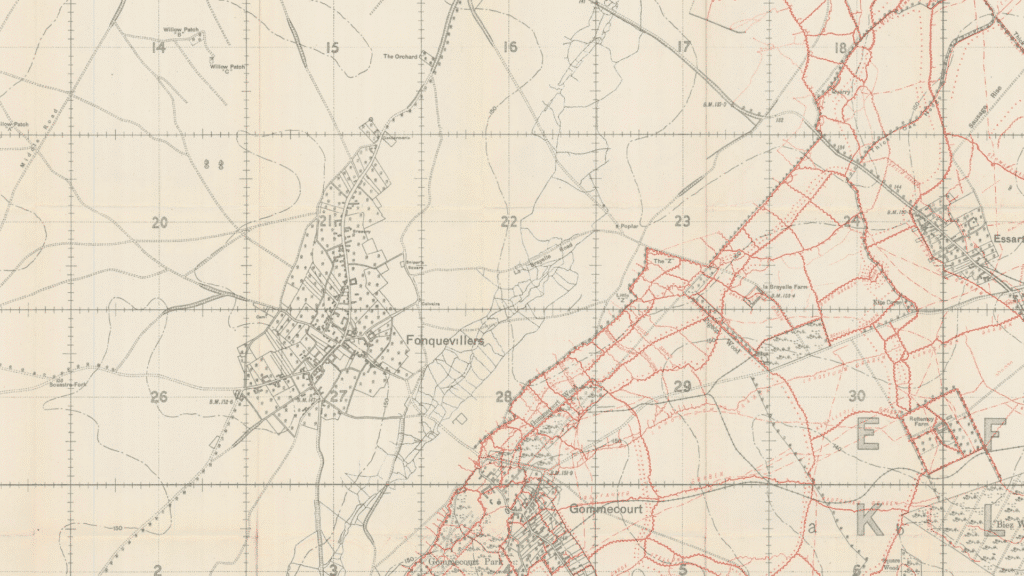

As part of the offensive there was one area that was earmarked to act as a diversionary attack to try and prevent the germans from sending reinforcements to the main attacks, that area was at Gommecourt on the northern area of the British Somme area.

The attack onto the Northern side of Gommecourt Wood was carried out by the 46 North Midlands Division of which the 5 and 6th Bn of the North Staffordshire Regiment were part. These were pre war territorial battalions but were also hard early war volunteers.

One of those Volunteers was my wife’s Grandfather, while he was a Derbyshire man he enlisted in Burton on Trent and found himself initially in the 5th Bn North Staffs but later with the 6th Bn. This would be his, as it would for many others of the regiment, first battle and the first time “going over the top”.

The battle did not go well for the Division that day for a whole variety of reasons, something that I’ll look at doing as an in depth and detailed blog post later.

Having walked over the battlefield and the specific ground that was the trenches of the 5th and 6th Bn North Staffs it is incredible to look south at the couple of hundred yards that had to be covered to reach the German trenches on the edge and inside Gommecourt Wood. Not a big distance but when you are weight down with kit and stores, rifle and ammunition that couple of hundred yards with some “German Bastard” shooting at you, that is a long way by anyone’s money, and it was probably even longer to get back to your own trenches at the end of it as well.

So, just a few things to take a moment and think on:

- The 1st July 1916 is the first day of the battle of the Somme.

- The numbers of casualties are very high on the first day but these are the numbers for dead, injured, missing and prisoners. It is a big butchers bill but look beyond the headline number.

- This battle of the Somme continues onto November 1916.

- While Gommecourt is a failure, there are significant successes on the first day, particularly in the southern areas.

My wife’s grandfather survived Gommecourt and the war, despite being gassed in the March/ April German Offensives of 1918, but all I would ask is that if you read this post, just take a bit of time today and think of those that were on the Somme in 1916.

Recreating the 1890 UP Saddle

Nearly 2 years ago I was contacted by Gerard Hogan, an Australian Saddler and conservator with the Australian Army Museum about my 1890 UP Saddle. Gerard wanted to get some more details about the Saddle and if possible if I could make paper templates of each of the elements of the saddle as there were a whole host of components and parts of the saddle that sparked interest for him.

One of the things that he was particularly interested in was that he wanted to see the feasibility of recreating it as the Australian Army Museum did not have a 1890 UP in its collection.

Having taken a large number of photos and made templates and paper traces for Gerard and now 18 months on I’ve been very fortunate to see the result of the work done by Gerard and others in Australia. The following information and photos have been provided by Gerard.

This saddle (Universal Saddle, Steel Arch, Pattern 1890.) depicts the Mk I without the split seat, and is fitted with the first pattern V-girth attachments (the MKI), and the MKIV numnah felt, as no numnah panels were fitted to the Mk I saddle.

The lancer pattern stirrup irons are fitted to this saddle, and these are original NSW Lancers stirrup irons made in 1885 England. The Mk I also had brass runners fitted to the stirrup leathers but we have to make these as it is impossible to locate brass runners.

However we forgot to add the leather caps to the side bars for this pattern of saddle. This meant this pattern, the Mk I, did not have felt numnah pannels fitted until the Mk II. The purpose of the caps protected the sidebars from damage and were held in position over the fans, by screws.

This was the period of time that the British War Office was experimenting with dispensing with the bulky horse hair pannels and using felt as an option.

Interestingly, the Mk I also had a small tab fitted into the slot on the rear edge of the seat on both sides. This tab looped under the foot of the rear arch as there was a small bevelled channel made into the timber side bar. The idea was to hold the seat down but it was soon found to be unnecessary. By the time of the Mk II introduced into service, this was dispensed with.

In service, the MkI had a brown saddle blanket fitted under the saddle and on top of the felt numnah Mk IV.

The Mk IV numnah felt had a front and rear small strap fitted and this was buckled to the front buckle on the saddle seat, and the rear buckle under the rear spoon of the rear arch, this was to hold the felt and blanket in place whilst in service.

It was found the saddle was too slippery in this manner on the horse and although the numnah felt could be ‘brought up’ into the front arch off the shoulders, the blanket often bunched up or fell out whist in service.

Therefore the MkII was fitted with the first pattern of felt numnah panels. This had a pouch to fit the front arch point and the rear fan had no brass loop fitted. This now provided the necessary grip on the brown blanket. Soon after this the numnah felt was then fully dispensed with.

Saddle Work Credits:

Arches were blacksmithed by WO2 Bruce Sinclair Ferguson RQMS (Australian Army History Unit, Australian Army) and are Mk I arches for the Universal Saddle, Steel Arch, Pattern 1890.

Leatherwork by Gerard Hogan the Regimental SaddlerTM

Timber side bars were made by Australian saddle tree maker Jeff Freeman.

Saddletree and leather assembly by WO2 Ferguson.

I have to say that I’m incredibly impressed with the work and effort that has been done to create the Saddle and I’m very pleased to have been able to help in this project for Gerard and the Australian Army Museum.

Build, Demolish & Defuse Weekend-26 & 27 April 25

Last weekend in April I was fortunate to find myself helping at the Royal Engineer’s Museum with their “Build Demolish & Defuse” event.

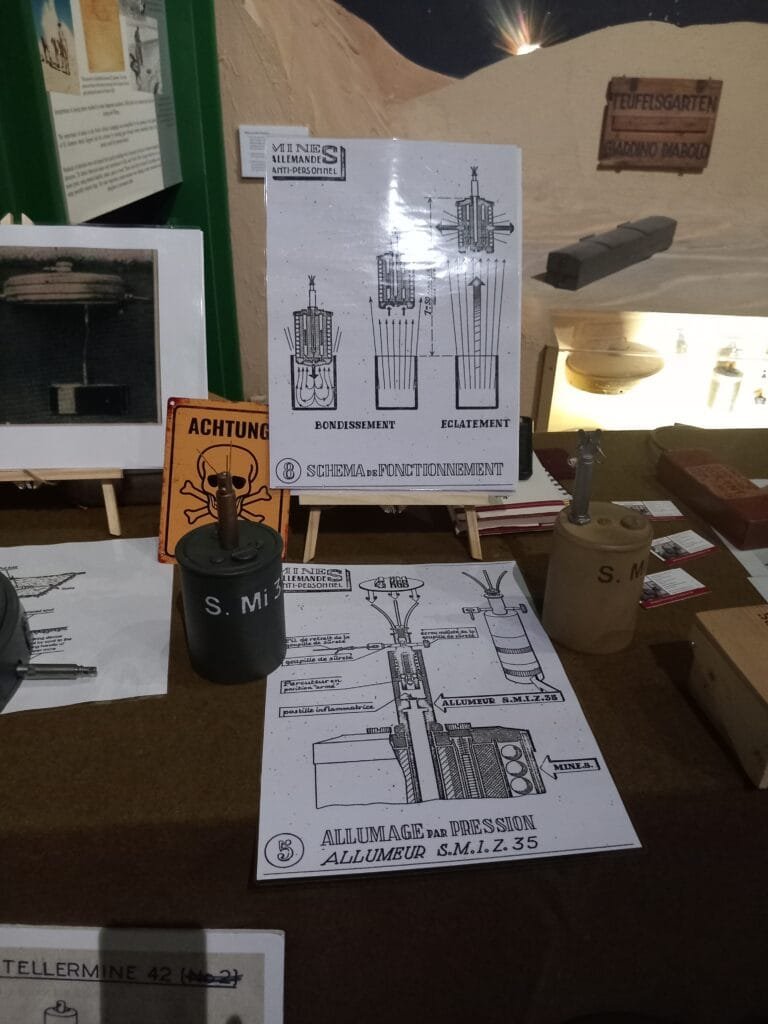

Once again I was there with the German Mines display. The difference this year is that we had some extra display items for the public to look at and handle. These helped to show the changes in the Tellermines (the 35 model through to the 42 model) (anti-vehicle mines) and also the changes in the S-Mine (anti personnel mines).

The other thing that I used on the display was a set of loaded 37 pattern Webbing and helmet, just to help give and indication of how much extra weight a soldier might be carrying and how with all of the kit they start to come close to the weight required to trigger one of the anti vehicle mines.

It was a busy weekend with a lot of engagement with visitors, a few of which I recognised from last year but there were plenty of first time visitors to the Museum as well.

It was great to chat with the visitors, some were keen to understand about the mines and one of the key things that helped to start the talks was explaining the differences between Mine clearance and bomb disposal.

For those that don’t know, Bomb disposal was a specialist task undertaken by dedicated bomb disposal units but mine laying and clearance could be carried out by any Sapper unit.

It was also great to meet up with Rob Crane from COPP Survey (www.coppsurvey.uk), who deals with the history of Combined Operations Pilotage Parties of WW2, I had previously met Rob at last years We Have Ways Fest where we had spoken about one of his family members that had been an instructor at 1 Training Battalion Royal Engineers that was located at Clitheroe. Rob shared some photos with me of the Mine Warfare training that was carried out at the time.

The above photo provided by Rob is a cracking display of mines and explosives that could be encountered by a WW2 Sapper and it is good to know that my display is in the same vein as this, so it’s good to know that I’m not far off the mark.

The photos provided by Rob have also helped to give me some ideas on how to further develop and evolved the display and the talks.

One of the other Living historians that was in attendance was Sapper Shand, who deals with the work and activities of the RE Tunnelling Companies in the Great War. We had a good chat discussing the variations and modification of tools required by the tunnellers and also the way that tools were modified by the RE Mounted Troops for to be carried in the RE Tool Bucket on the saddle of a horse.

Sapper Shand runs his own facebook group – RE Clay Kickers so if you are interested in the Great War Sappers or in particular in the role of Tunnellers then give him a follow and like.

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61558148302748

One of the other visitors was an individual taking a lot of photos, once we got chatting it was interesting to hear how he, Bob, would visit events to get photos from WW2 events and re-enactors. Being happy to oblige we took a number of photos for Bob’s facebook group, one of which is below.

The following is a link to Bob’s group https://www.facebook.com/BobsFighting40s

It was a cracking weekend with a lot of interaction with the public and it was good to know that the changes to the display worked and worked well. Now looking forward to a future visit back to the RE museum.

Visiting the Sappers at Railway Wood

During my last 2 weeks in Belgium I thought I would take time on the weekend to visit the Ypres area to do a bit of battlefield recces and also to visit some of the memorials.

One of the memorials that I always try and take a bit of time to visit when in the area is the Royal Engineer Graves Memorial for the men of 177 Tunnelling Company Royal Engineers. I’ve got into the habit of it being a location that I visit around about lunchtime and try and take a bit of time just to sit down and take in the location, wildlife and to give a moment to think about the men that fought underground.

Its an interesting memorial as it has a Commonwealth War Grave Commission Cross on it but there are no actual graves as it commemorates 12 men of the Tunnelling Company that lost their lives underground and were not recovered.

The other thing is that of the 12 men named on the memorial, 3 are infantrymen attached into the company. Having infantrymen attached into Tunnelling Companies was not unusual it could have been done for several reasons:

- The individual had mining experience from his civilian job.

- They were from a pioneer unit and allocated to work with the Sappers.

- They were from a Infantry unit in the area and were tasked to work with the Sappers as part of their “Working party” duties.

Either way, what ever the reason, their job underground was just as dangerous as for the Sappers that they worked with and they rightly are commemorated on the memorial.

But Railway Wood is worth visiting for more than just the RE memorial.

If you are interested in Tunnelling and the exploits of the men who fought in a world that I just cannot fully comprehend, where Engineering skill and specialist knowledge are vital to keeping you alive as you work and then having to learn the skills of listening for the enemy and counter-mining, then the chances are that you will be thinking of the exploits of the Tunnellers at Hill 60 or Lochnagar Crater on the Somme. Those are really important sites and the exploits are incredible but I would suggest that perhaps you should consider Railway Wood and the local area.

Why? Well to put it simply there is a bloody lot of big holes in the ground all around the area!!

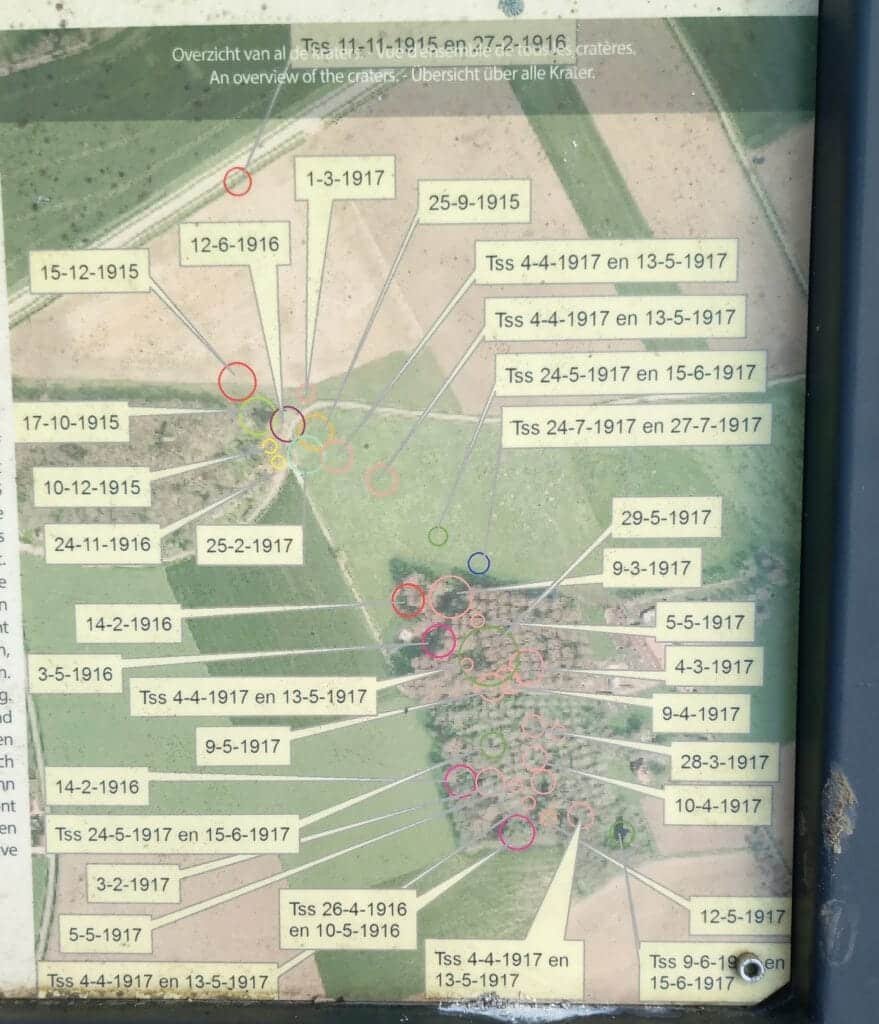

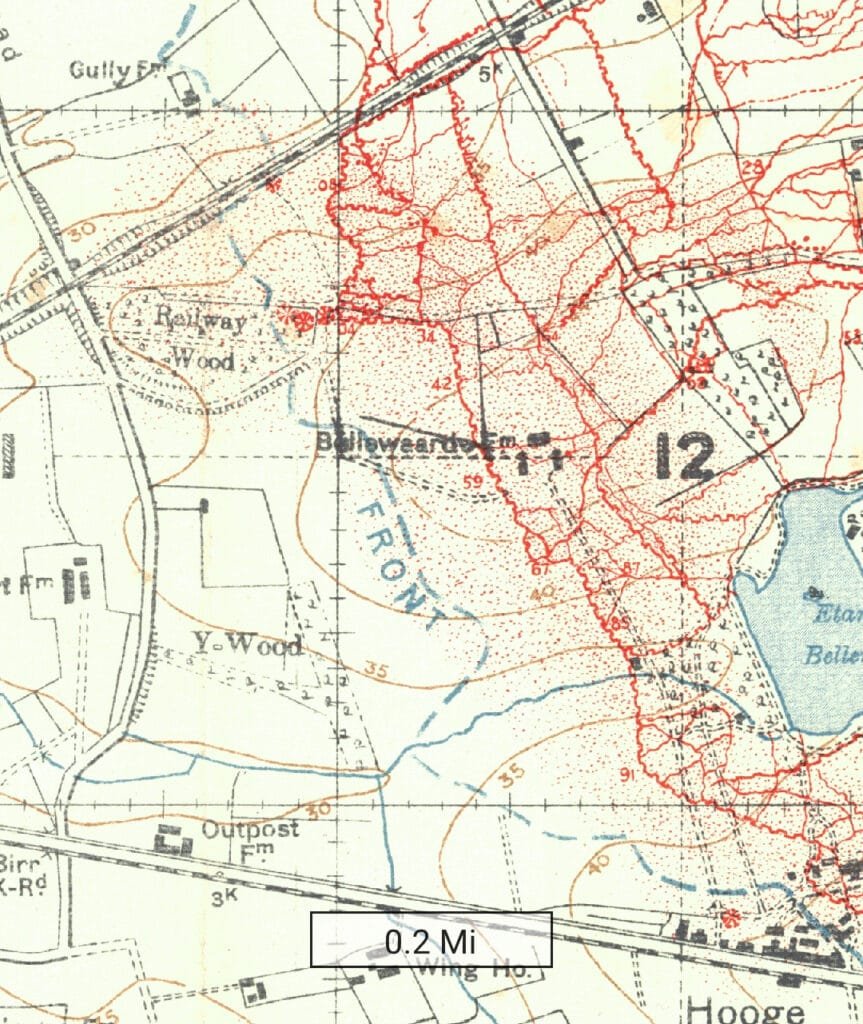

The 177th Tunnelling Company was active in the Ypres area between Autumn 1915 through to August 1917, with a hard and dangerous fight underground with British and German miners. The area is covered with over 33 Craters created by both sides and covered from Hooge across to Railway Wood

177 Tunnelling Company RE was formed in Jun 1915 and in the Autumn of 1915 it moved to Ypres and built dugouts in the ramparts of the town, this was done from September to November 1915. From November 1915 the Company moved out of Ypres and took over responsibility for mining and counter-mining activity in the Railway Wood to Hooge area and particularly with work under Bellenwaerde Ridge near Zillebeke.

Screenshot taken from the Linesman mapping software of the area covered by 177 Tunnelling Company RE

Looking across the crater formed on 3 May 1916 towards the RE Memorial. While mining and counter-mining was the main focus of the 177 Tunnelling Company RE they also built and developed an underground Forward Accommodation Scheme at the rear of Railway Wood.

From the photos you can see some of the evidence of the work of the German and British miners through out the wood and it is worth the wander to step away from the main paths onto the smaller tracks to get to see the size and scale of the craters.

The wood also has a lovely memorial to the London Scottish and it is worth just taking a short break to consider how much fighting occurred here across the war both on the surface and below the ground.

So while the craters at Hill 60 and the Caterpillar are important and visually impressive, I would recommend that if you want to look at and study some vital RE Tunnelling works then visit the memorial and the Craters between Railway wood and Hooge.

Quick Update – Adding to the WW2 Display

At the moment I’m being kept busy with the transition from being overseas to coming back home to the UK.

As part of the change there is also a bit of preparation for events and displays for the coming year, and one of the plans is to work on improving the talks and briefs. In particular there has been some work on the Great War saddlery and a the RE tools, but one that will be in use first will be for the WW2 Display on Mine Clearance.

Previously we have used display boards and extracts from the Mine Manuals, however I’m now managed to get some new display items that can be handled. Previously we only had the the Tellermine 35 as a display item but now we can add the Tellermine (S) and the Tellermine 42.

On the Anti Personnel Mine area we also have an increase but I’m also working on adding another couple of items to help with the display, but more to come on that once I’m back in the UK on a full time basis.